On Jan. 23, 1939, cranes lifted the two massive lion sculptures on the Lions Gate Bridge into place.

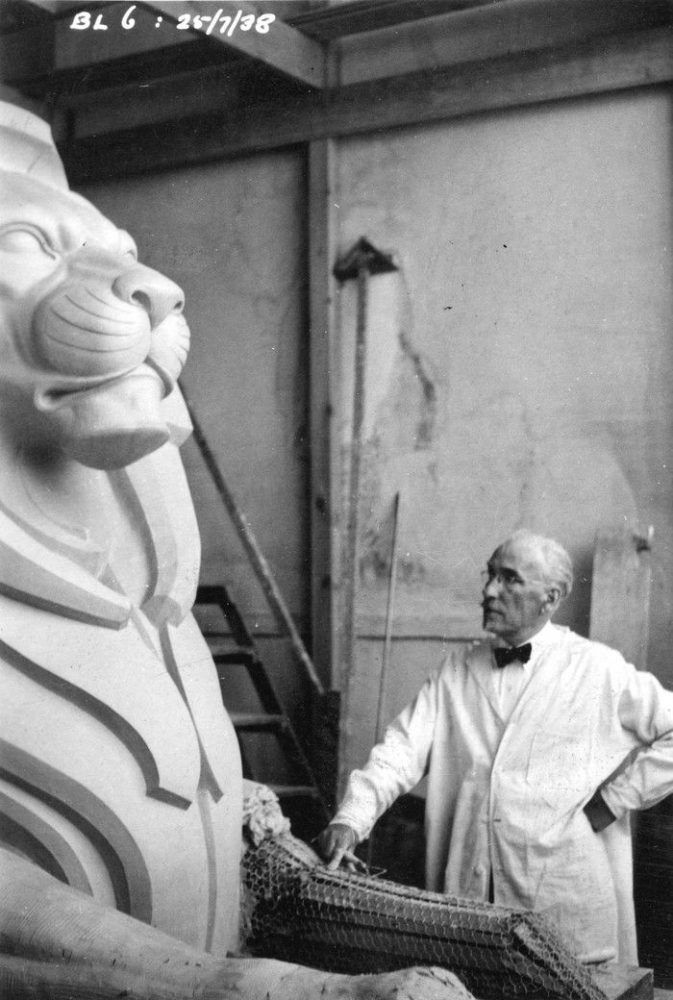

“Sculptor Charles Marega was just too nervous to watch, for fear that something might happen to his seven-and-a-half-ton pets,” said a story in The Province.

“But as early sunlight gilded the crest of the North Shore peaks of the same name, derrick-trucks shifted the bodies without a hitch, elevating them to the pedestal and lowering them gently into place.

“Heads — each of which weighs two tons — were jockeyed into place later.”

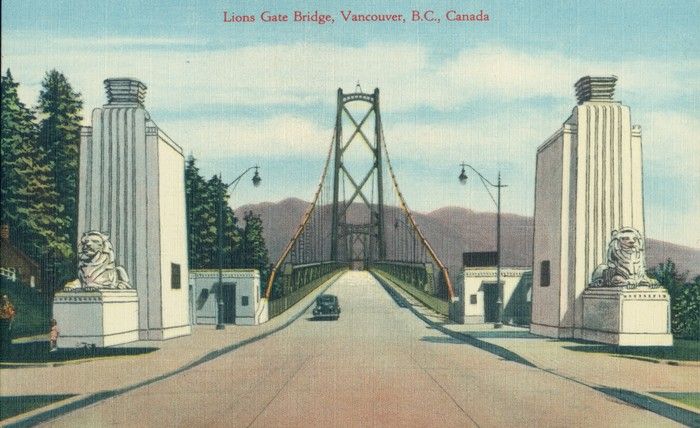

The installation of the lion sculptures was the final stage in the construction of the Lions Gate Bridge, which opened to traffic Nov. 12, 1938, but wasn’t officially opened until the royal visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on May 29, 1939.

Sadly, sculptor Marega didn’t make it to the official opening — he dropped dead of a heart attack after teaching a class at the Vancouver School of Art on March 24, 1939. He was 63.

The native of Italy was Vancouver’s most successful sculptor in his day. He did the Warren Harding and David Oppenheimer memorials in Stanley Park, the statue of Captain George Vancouver at City Hall, and the Joe Fortes memorial fountain in Alexandra Park.

But the lions are his most-viewed work. Millions of people drive by the sculptures on the south side of the Lions Gate Bridge each year, a grand entrance to the elegant suspension bridge that soars above the First Narrows to the North Shore.

Marega almost didn’t get the commission, though. The bridge was built by the First Narrows Bridge Company, a British firm owned by the Guinness family. In 1931, it had purchased 16 square kilometres in West Vancouver, and it wanted to lure the masses to its British Pacific Properties development.

It hired Monsarrat and Pratley engineers of Montreal to design the bridge, and Monsarrat and Pratley wanted to use a Montreal artist. But the local person in charge of the bridge project, A.J.T. Taylor, successfully argued to use Marega.

Taylor lived in a penthouse at the top of the Marine Building in the 1930s. He loved Marega’s lions so much that the maquettes (small sculptures/studies) for the lions ended up on the terrace of the penthouse.

Still, there were disagreements. Marega wanted to do the lions in bronze, but they wound up being made of concrete.

“It just became a cost issue when they were building,” said heritage expert Don Luxton, who co-wrote a book on the Lions Gate Bridge with Lilia D’Acres. “They built everything as cheaply as they could. First of all, (the bridge) is a private enterprise. And secondly, it’s the Depression.”

The concrete lions are hollow, and were built in two parts, the body and the head.

“Marega wanted to do two moulds, so that you could have tails go different ways, but they wouldn’t pay for it,” he said. “So they did one mould, and the tails both go the same way.”

Initially, Luxton said, there was talk of doing a couple of statues of First Nations men at the bridge entrance, but the lion statues were an obvious choice.

“They were symbolic,” said Luxton. “They refer to the mountains (known as the Lions), of course, but they refer to the British Empire, they refer to British heritage. It was British money that built the bridge, after all, so British Properties. So why wouldn’t you do lions?”

Marega did a plaster mould in his studio on Hornby Street, where Robson Square is today. Then they cast them in concrete on the site, with the mould inside a big wooden box that was dubbed “the coffin.”

The casting was also done upside down, “because then they could hollow it out” to make it lighter. Workmen from Stuart Cameron and Co. built wheels underneath the wooden framework to roll the lions from the shed where they were cast to their resting place on either side of the bridge.

Silver coins were buried under the paws of the lions by the workmen, and a nickel was placed under the tail of the lion on the west side. Luxton said Taylor placed his own time capsule inside one of the hollowed-out lions — “his version of the events leading up to the Lions Gate Bridge, and his baby shoes.”