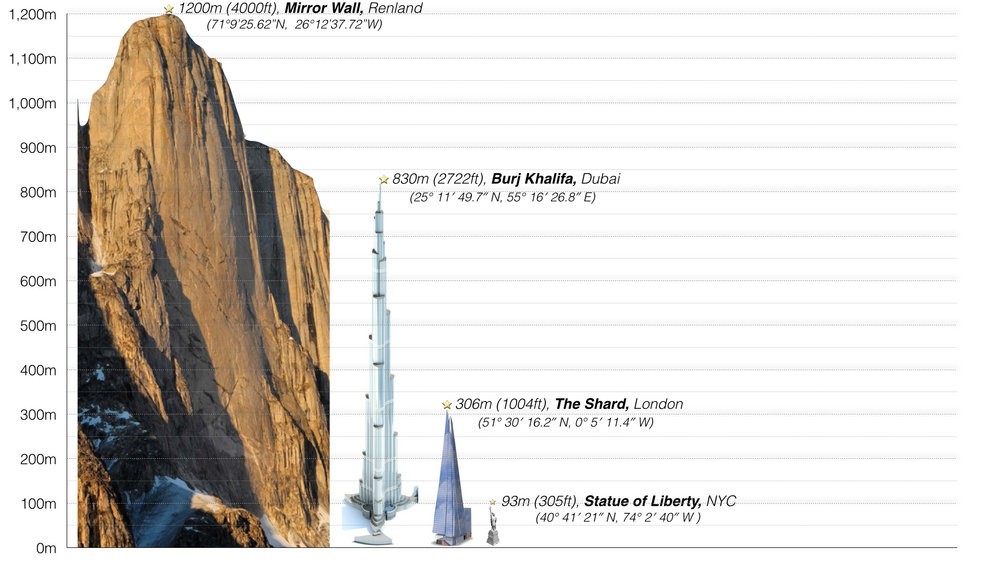

In the summer of 2015, five climbers spent nearly a month at the edge of eastern Greenland’s Edward Bailey Glacier, working their way up a 1,250-meter granite wall that had never been climbed head-on. Eleven years on, the first ascent of the Mirror Wall’s northwest face still stands as one of the more direct and uncompromising big-wall routes in the Arctic.

On July 27, after 15 days on the face, Leo Houlding sent a short message to his support team: “We nailed it.” The route, Reflections (5.12c A3+, 1,250 m), had gone from glacier to summit with minimal drilling and an emphasis on free climbing, despite worsening weather and a record snow year. Houlding, along with Matt Pickles, Matt Pycroft, Waldo Etherington, and Joe Mohle, arrived in Greenland on June 25. Their objective was the unclimbed northwest face of the Mirror Wall, a face taller than El Capitan and far more remote. Unlike earlier ascents on the flanks of the wall, this line aimed straight through the center.

“The Swiss climbed the two most obvious lines,” Houlding said later, referring to the 2012 routes on either side of the face. Those climbs traced natural weaknesses along the edges. “We wanted to climb directly up the center.” The only viable line without extensive drilling, he explained, cut up the left side of the main face before linking into the headwall via a difficult aid traverse above halfway. Reaching the wall was an expedition in itself. The team hauled heavy loads across loose, knee-deep snow and through crevasse fields that shifted daily during the melt. Serac collapses and avalanches were constant background noise. After establishing base camp, they spent three days fixing ropes to Bedouin Camp, 260 meters up the wall.

From there, the team lived on the face for 12 nights, climbing under continuous daylight, often in mist or light snowfall. They established 25 pitches; 23 were climbed free. The climbing ranged from sustained free cracks to wide sections, traverses, and long stretches with few features. Houlding described it as “hard free, hard aid…grand traverses and complete blankness.” Conditions deteriorated during the final week, but the team continued upward, topping out at 4:20 a.m. on July 22 in light snow. They rappelled the route, cleaned their gear, and flew out by helicopter on July 28.

About the climbing, Pickles wrote in the American Alpine Journal, “Living up to its name, the central Mirror Wall is blank. With limited time and unstable weather, a wrong turn on the huge expanses of featureless granite could easily have led to failure. Taking advantage of the 24-hour daylight, and working in teams of two, we climbed around the clock to get through the harder pitches. We climbed until we were exhausted, rested until we recovered.”

Although the team had strong individual résumés, none had previously been part of a big-wall expedition first ascent of this scale. Houlding acknowledged that gap but saw it as a strength rather than a liability. Mohle brought experience from remote trad routes; Pickles was a high-level sport climber with El Cap ascents behind him; Etherington specialized in rigging and rope systems; Pycroft documented the climb while contributing on the wall. “All very talented and experienced in their fields,” Houlding said, “but new to this kind of project.”

Houlding later referred to the Mirror Wall area as a “grown-up playground,” a phrase that captured the broader experience rather than the climbing alone. The moraine travel, crevasse navigation, camp construction, and route-finding all came without external support. “No rules, no referees and no help if anything goes wrong,” he said. “You’re entirely responsible for your own actions.” The rock quality varied. Much of it was solid but cluttered with loose material in cracks and on ledges. Higher on the wall, the granite improved, including one corner formed entirely of quartz crystals. “I’d never climbed anything like it,” Houlding said.

The low points came early, particularly the glacial approach and a steep, unstable snow slope at the base of the wall, which the team had not brought enough rope to fix. The high points came in unlikely places: solving a blank section above Bedouin Camp free and onsight, and a six-hour A3+ lead through the night without drilling. The route required restraint. Two blank sections dictated the use of rivets, including a traverse that needed 10 to reach the final line. In total, the team placed 11 lead bolts and rivets and 30 belay and camp bolts. “The harder climbing was reasonably safe,” Houlding said. “The aid was hard, but never too dangerous.”

More than a decade later, Reflections remains unrepeated, a direct line through the center of one of Greenland’s largest granite faces.

The post The First Ascent of Greenland’s “Arctic El Cap” Mirror Wall appeared first on Gripped Magazine.