It has been 56 years since Patrick (Paddy) Paddon walked into the woods in Colchester County on a deer hunting trip with his father and uncle.

Nov. 29, 1969 was also the last time anyone saw Patrick, who was 17 at the time.

He and his relatives were supposed to be out for just a few hours that morning. They went into the woods on Pembroke Road in Burnside not far from a farmhouse owned by a family friend, and they were supposed to meet at that house at noon.

Patrick’s father, Bernard, and uncle, Neil, returned, but Patrick didn’t.

When he still wasn’t there by 1:30 p.m., they drove around the area and to Stewiacke and Truro, but there was no sign of Patrick, a Grade 11 student at the former Prince Andrew High School in Dartmouth.

The two men saw another hunter who told him he had met Patrick on a road at 2:45 p.m. and he had asked for directions back to the farmhouse.

But he didn’t show up, and RCMP were called. A search started the next morning, after more than 35 centimetres of snow had fallen.

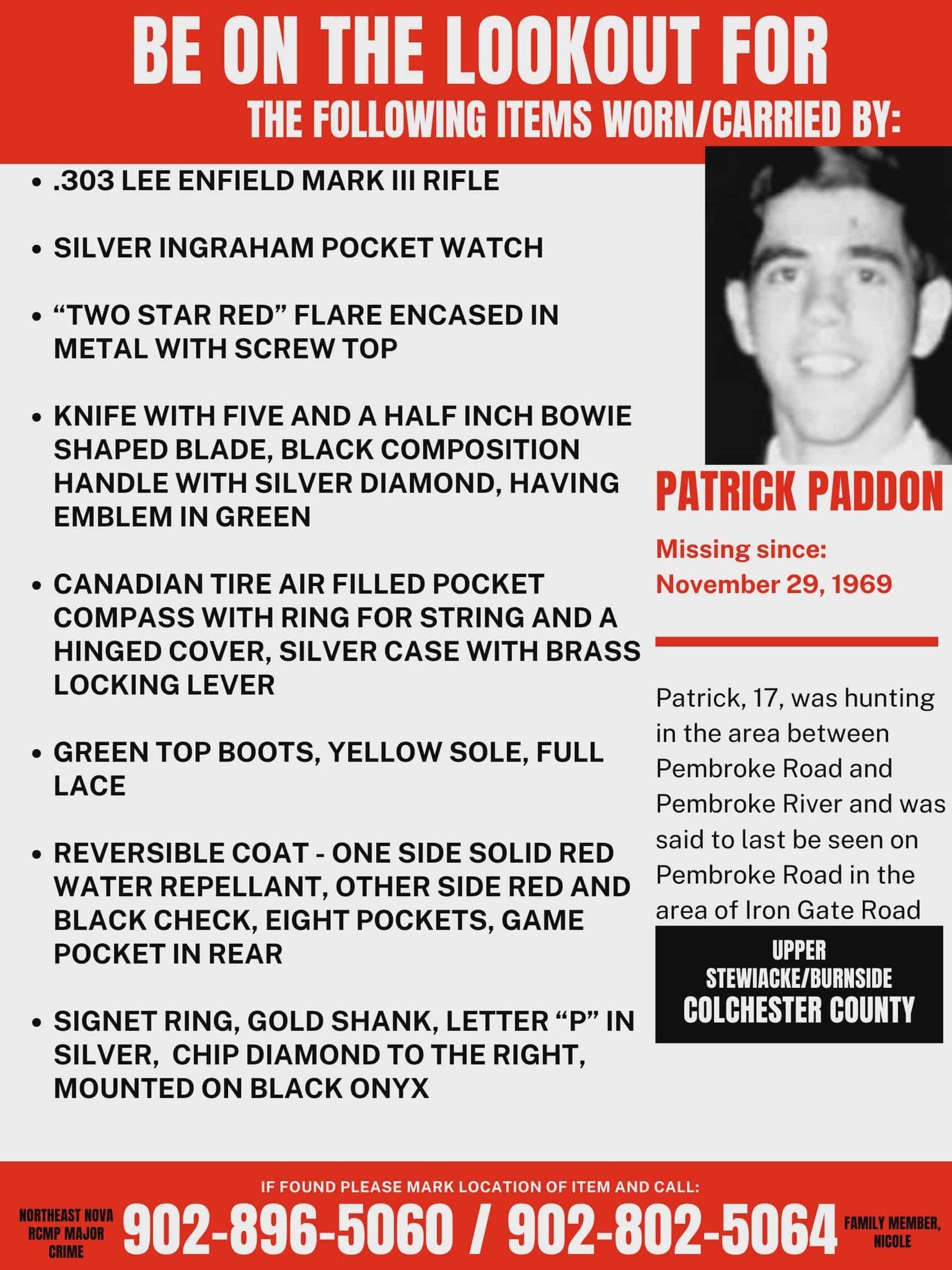

Patrick was prepared for the day in the woods. He had food, a safety flare, a compass, a pocket watch, his rifle and a knife. He had matches coated in wax to waterproof them in the butt of his rifle. He was dressed warmly and had a reversible coat that was water repellent, which would have been useful with the snow that fell.

Searchers on foot, in a helicopter and on snowmobiles found no trace of Patrick or any of his belongings. Up to 80 volunteers, military members from bases in Summerside and Shearwater, and staff from the Department of Natural Resources searched an area of 72 square kilometres, with only one set of possible footprints found. On Dec. 8, the search was called off.

While social media has a way of keeping missing person cases alive through “on this day” memories or just general discussion, unless one knows about historical cases people are unlikely to see them come up in conversation.

But for relatives of Patrick, his disappearance is always there. His niece, Nicole Balcom, wasn’t even born when Patrick went missing. She said the disappearance is something the family talks about regularly, but there have never been any answers.

“His picture is in our hallway, but there has always been the question of what happened to Uncle Paddy.”

She said her mother — Patrick’s youngest sister — said there was no panic at first because he knew the woods.

“Mom was like, ‘Oh, he’ll be back,’ and then he just never was, and nothing of his was ever found.”

Balcom said her grandfather and uncle believed another hunter accidentally shot Patrick and didn’t want to admit it, but police didn’t share that suspicion

“Our family’s main thought was that if he was spotted on the road toward Truro, why would he have gone back into the woods if he was already on the road and already late?”

She said that even if Patrick saw the buck of his dreams from the road, he likely wouldn’t have gone deep into the woods.

“Did he get to Truro? Did he get on the highway? There are no answers and no closure.”

Family in Ontario remember waiting to see if Patrick was running away and heading to see them.

The woods are dense in that part of Colchester County, and they are still popular with hunters.

Balcom and the family made posters about the case to put up this year in the general area and in online hunting groups, not only as a way for people to know of things to be looking for but in case they had found something years ago.

“We’ve all definitely had conversations about what could have happened, but it’s all theories, and unless we find any evidence we don’t know that he didn’t leave those woods,” she said.

“In the dream world, we would love to know that he got to Truro and hitchhiked and went out west somewhere and lived his best life, but in reality . . . that doesn’t make logical sense.”

Related

She said Neil and her uncle — Patrick’s brother-in-law — frequently went to the area looking for clues or signs of what happened to the teen, including by helicopter.

“My (great) uncle felt responsible as he was the last one to see him.”

She said the family is still hoping for closure, although generationally she thinks people approach that differently.

“The younger generation has heard of cases being closed (with evidence found) and we hope for that, while the older generation kind of has their (version of) closure with ‘He’s gone, he’s dead, and we’ll never know how it happened.’”

Patrick was declared dead years ago.

“All it would take would be to find the metal from his gun and then we would be able to close the book and say, ‘He never left the woods,’” Balcom said.

She said that because he had several items with him, they still hope someone may remember finding one over the past six decades.

He had the following:

- .303 Lee Enfield Mark III rifle

- Silver Ingraham pocket watch

- Two Star Red flare in a metal tube with a screw top

- Knife with a 15-centimetre Bowie-shaped blade and a black composite handle with a silver diamond and green emblem

- Canadian Tire air-filled pocket compass with a ring and hinged cover, in a silver case with a brass locking lever

- Green-topped boots with yellow soles

- Reversible coat, red and water-repellent on one side, red-and-black checked on the other

- Signet ring with a gold shank, the letter P in silver with a chip diamond to the right, mounted on black onyx

“What if somebody 30 years ago, for example, found his ring and just put it in a box and haven’t thought anything of it since? If we find one item, then we’ll know he never left the woods,” Balcom said.

She and her partner walked the area when putting up posters up in the fall.

“There are a lot of spots you can’t walk in 10 feet from the road because it’s so dense,” she said. “In the police report they talked about a swamp, and that’s the only area you can see well.”

Balcom said walking through that area felt “heavy.”

“This place holds a lot of memories of sad, terrible times for the older generation in our family.”

She said she just wants people to talk about the case and hopefully trigger a memory.

Balcom said that while her grandfather’s and mother’s generations believe Patrick was either shot by another hunter or moved out west, she doesn’t have any real theory of what happened. She doesn’t think that he hunkered down for the night and died from exposure because he had been on the road and was well-prepared to bed down for the night if necessary.

“I don’t think he was lost for days and starved to death,” she said. “I don’t think that’s a possibility.”

A couple of years ago, someone in the family asked for and received a copy of the RCMP file, so Balcom asked for a copy and did a video interview with her great uncle, Neil.

“His memory was not what it should be,” she said. “I was asking about what he remembered, and we didn’t get anywhere with that.”

Neil died in September. Not long after, Balcom got a message from Terynn Boulton, who saw a post by Balcom from the previous year on the Halifax Regional Police Facebook page in which she mentioned Patrick’s disappearance.

Boulton has had an interest in missing children cases for years, since she first heard about the disappearance of Tania Murrell in Edmonton in 1983. Murrel was six. Boulton was eight.

“That impacted me. I was horrified that children could go missing. . . . I guess that was a turning point in my life.”

She checked over the years for any news of whether Tania had been found. As the internet became a tool, she would check the Missing Kids Canada website periodically for updates. She started to do more research and eventually started the We the Missing website that focuses on missing children.

She saw the post from Balcom and made contact.

Boulton went through the RCMP file and the family’s recollections to create a full narrative on the website of Patrick’s disappearance and the subsequent search. She said she wants to make more people aware of the case.

“It’s not that people don’t care, but it’s from 1969 and people don’t really know, even if they know he’s missing, how they can help or how he’ll ever be found if he hasn’t been by now,” Boulton said.

“You can’t find missing people if no one knows they’re missing. If Patrick did die in the woods, hunters could have already come across something related to him and not even know,” she said.

“The longer it goes, the less likely it is that anything will be found, and we’re not going to find him if no one knows he’s out there. His father and mother have passed, and now his uncle.”

Bouton said some things seem odd to her, like Patrick being last spotted on the road after the agreed-upon meeting time but not walking back along the road, and being well-prepared to survive a night in the woods if he did get lost.

In 2007, remains were found in the general area but they were determined to belong to someone else who was missing.

RCMP spokeswoman Cindy Bayer said there have been no recent tips in Patrick’s disappearance, which is still considered a missing person case with no indication of a homicide.

While the province doesn’t have a cold case team, open files are reviewed regularly.

“There are still protocols where you have to look at a file within a certain number of years; we don’t just let them sit there,” she said.