Behind the three-storey rolling doors of its prototype factory in Delta, a Metro Vancouver company is fine-tuning an approach to prefabricated construction that it believes could be key to solving Canada’s housing crisis.

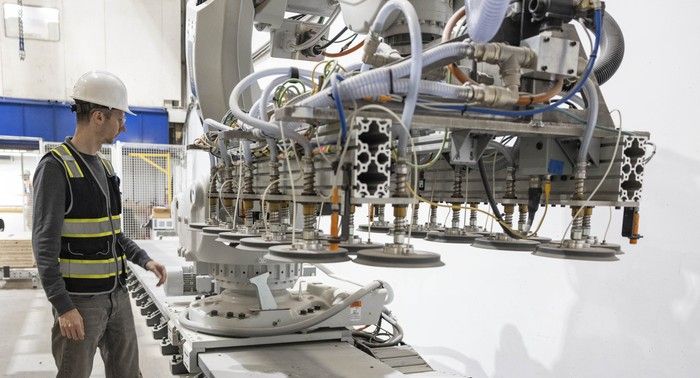

Intelligent City is using massive industrial robots and advanced techniques in mass-timber construction to produce complete floor and exterior wall sections for a nine-storey apartment building that will be assembled in the Toronto suburb of Etobicoke.

In the middle of the factory, a pair of automated machines on parallel tracks engage in a precisely choreographed dance to the tune of detailed digitized plans, laying down layers of glue and nailing elements together to assemble floor panels.

Floor sections are the size of one apartment unit, complete with ducting and conduits for heat, wiring and plumbing. Wall sections include insulation, membranes, windows and exterior cladding.

“It’s industrialized construction,” said O.D. Krieg, Intelligent City’s president.

The Etobicoke project is Intelligent City’s second major project using the method. It manufactured the components for its first a year ago — a nine-storey, 80-unit affordable housing project on Frances Street for the Vancouver Native Housing Society.

Once built, components for each storey of the building are flat-packed onto five transport trucks for shipment to Etobicoke, where a small crew can assemble them in about a day, Krieg said.

“At this point, it’s going faster than we thought,” Krieg said, so much so that the Delta factory has turned into a bottleneck “because we are not shipping fast enough.”

The time saved by Intelligent City’s method — which is about four to six months over traditional concrete construction — can help governments meet the ambitious targets they are setting for home building.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has committed to doubling the rate of new home building to 500,000 units a year over the next decade. During this year’s election campaign, he pledged $25 billion in federal financing to builders of prefabricated homes for “innovative” projects.

Prefabricated construction isn’t new. Factory-built modular houses and multiplex buildings have been produced for decades.

B.C. pioneered mass timber construction with buildings such as the Brock Commons student residence at UBC, which was completed in 2017.

Krieg said Intelligent City’s process is the next step, with automation making it possible to deliver more prefabricated components to building sites.

“We can’t just suddenly have twice as many builders and twice as many construction workers,” Krieg said. “The only chance we have is that we prefabricate buildings, we reduce construction time, and we do the same amount of labour that we have, just twice as efficient.”

Carney’s federal push follows steps B.C. has taken with the passage of Bill 44, which requires municipalities to allow multi-unit dwellings on single-family lots, and commits to fast-track modular housing as a way to speed up the construction of new homes.

Those measures have brought about “a pivotal moment” for B.C.’s manufactured-housing sector, said Paul Binotto, director of the industry advocacy group Modular B.C.

“What Bill 44 has done is it’s allowed the volumetric (builders) to start looking at that middle sort of neighbourhood-friendly density,” Binotto said. “And for that, we’re well positioned.”

The term “volumetric” refers to the factory prefabrication of buildings in boxlike modules that can be up to 95 per cent complete before arriving on site. This approach is used by most of the 18 factories producing prefabricated homes in B.C., Binotto said.

Binotto said exact numbers are hard to find, but industry groups estimate prefab methods account for about 4.5 per cent of homes built in B.C.

Modular B.C.’s objective is to raise that number to 25 per cent.

The advantages of manufactured and modular components don’t end with being quicker, Binotto said. A University of Alberta study estimated that the manufacturing process produces 43 per cent fewer carbon emissions that traditional, stick-built construction on site, and results in 50 to 70 per cent less construction waste.

Modular B.C. has set up a mayors committee of five municipal leaders, chaired by Burnaby Mayor Mike Hurley, to help advocate prefabrication in building more affordable housing.

Binotto said that means working with building officials on guides and checklists for the approval of prefabricated homes.

“These have all been issues that have, in the past, slowed the process down,” Binotto said. “Permitting is a big part of it.”

The upfront costs for methods of prefabrication such as mass timber appear to be higher, although their promise of speed and consistent quality can bring overall costs down.

Construction is still geared toward “one-off, one-at-a-time thinking, but the industry needs to focus on procurement processes that emphasize repeatable elements in several buildings,” said industry adviser Chris Hill.

“That is where modular builders excel. So, getting a better understanding of cost. Mass timber, off-site construction, all these elements need to prove themselves that they can reduce cost.”

Krieg said Intelligent City’s system can be more cost-effective than concrete construction, in part because it uses less concrete in the foundations that all buildings need.

“A timber building is about half the weight of a concrete building,” Krieg said. “And then the construction time is faster, so that influences all other line items.”

Timber buildings also use less drywall and other materials, he added.

However, Krieg acknowledges that manufacturing a building in Delta and shipping it to Toronto isn’t really sustainable or cost effective. The idea behind Intelligent City’s project was to gain exposure in the Toronto market.

“We have (had) lots of conversations with other developers and we are raising money to set up a factory in Toronto as well,” Krieg said. “And we’re seeing traction here in Vancouver. We want to expand here as well.”

Another catch is that although a number of B.C. companies produce the cross-laminated timber panels used in mass-timber construction, Krieg said they’ve turned to a supplier in Austria to remain cost competitive.

“Europeans are pricing their materials quite aggressively,” he said.

The industry will need more investment to make local producers more competitive, he added.

“We have the materials, we have the sawmills, we have the (cross-laminated timber) suppliers,” Krieg said. “We can build this all in Canada.”