A new advocacy group for Canadians jailed for crimes they didn’t commit has taken up the cause of a Kamloops man who spent 26 years behind bars for first-degree murder of a woman more than 30 years ago.

Ontario-based Miscarriage of Justice Canada is urging the B.C. government to hold a retrial in Gerald Klassen’s case as ordered in 2022. Without a retrial, the group said, Klassen can’t prove his innocence or get compensation.

Then federal justice minister David Lametti ordered the B.C. Supreme Court to retry the case, about two weeks after a ministerial review determined Klassen’s murder conviction was a “likely miscarriage of justice.”

It was thanks to UBC’s law school’s Innocence Project that worked on the case for years and found prosecutors didn’t fully disclose evidence to the defence. It also found the B.C. Coroners Service pathologist changed his testimony at trial from the preliminary hearing to opine the victim, Julie McLeod, 22, had been sexually assaulted and beaten at Nicola Lake.

More than a year after Lametti’s order, B.C.’s attorney general entered a stay of proceedings against Klassen, meaning the charges would be put on hold for a year before being dropped, instead of announcing a retrial and likely acquittal.

A retrial “is what should have happened,” said Myles Frederick McLellan, executive director of Miscarriage of Justice Canada. “The province instead decided to wash their hands of it, which we think is wrong.”

The lack of retrial denies Klassen the chance to clear his name by having all the evidence heard to determine if prosecutors proved murder beyond a reasonable doubt, which wouldn’t be likely, said McLellan.

And it also makes it more difficult for Klassen, who’s now 65 and spent from ages 35 to 60 in jail, to be compensated for the wrongful incarceration, because civil lawsuits are difficult to prove, he said.

“Mr. Klassen spent more than half of his adult life in jail and he’s entitled to be compensated and fully compensated,” he said.

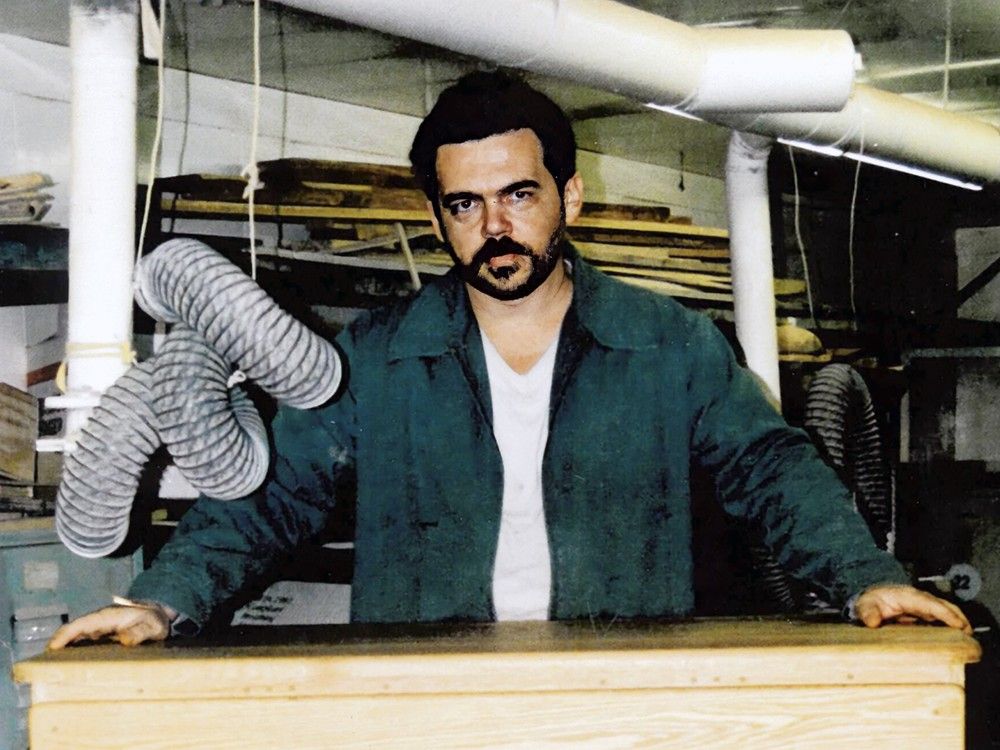

“A retrial helps dispel the public stigma” he has faced as a convicted murder. A welder by trade, he has trouble getting or keeping jobs when employers discover his life story, according to court documents.

Klassen filed a lawsuit this year against the B.C. prosecutor are his 1995 murder trial, three RCMP officers, the Coroners Service and its expert pathologist witness, and former B.C. attorney general David Eby, as well as the federal attorney general.

The lawsuit seeks unspecified damages. It was filed in April and amended in September, but none of the defendants has filed a response.

A spokesman for B.C. Attorney General Niki Sharma said she wouldn’t comment while the case was before the courts. The ministry didn’t say why it hasn’t filed a response to Klassen’s lawsuit, months after the deadline passed.

Miscarriage of Justice said in a news release that if the province continues to deny the retrial, the “integrity of the entire review process is undermined.”

It said the federal-provincial-territorial guidelines on compensation for wrongful convictions call for redress once a person has been publicly cleared.

It asks B.C. to allow a new trial, discuss compensation with Klassen and his lawyer and “affirm its commitment to transparency and fairness in the miscarriage of justice review process.”

The lawsuit says Klassen has suffered psychological distress, pain and suffering and loss of income.

At the preliminary trial, the pathologist witness said McLeod may have died of hypothermia or strangulation, but likely hadn’t drowned — and that he couldn’t determine cause of death.

At trial, he stated McLeod had died as a result of being beaten while intoxicated and possibly hypothermic, and that was accepted by the judge. The judge used that testimony to instruct the jury, who relied on it to convict Klassen, said the lawsuit.

It alleges the police, prosecutors and others had “negligently, maliciously and/or unlawfully violated” Klassen’s rights when in 1993 to 1995 they arrested, charged, tried and convicted him.

And it alleges Eby denied him a new trial as an attempt at “avoiding public embarrassment and a potential lawsuit and being held accountable” for Klassen’s wrongful conviction.

Several other pathologists that reviewed the case said they could not definitively say what caused McLeod’s death, the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions says.

“Expert evidence obtained after the trial indicates that there was no forensic evidence to support a conclusion that Ms. McLeod had sustained a beating,” according to the lawsuit.

McLeod was found dead, with a mouth wound, half naked and half in the water of Nicola Lake near Merritt on Dec. 16, 1993, the day after she and Klassen had been there together.

Klassen said he had been with her and her boyfriend at a hotel bar earlier and after dropping her boyfriend at home, they visited a bootlegger and went to the lake, where they drank beer and talked, later had sex, and then had an argument, the claim said.

Klassen told police he had pushed her during the argument and she fell but she was alive when he left her there after she refused a ride. He has always denied killing her and was denied parole because he maintained he was innocent.

Th prosecution theory was that he violently sexually attacked her, beat her and dragged her body to the lake. She had no bruising of her breast or genitals and court heard Klassen’s wife testified he had returned home that night at 11 p.m. with no wet clothing or any signs that anything unusual had happened.

Canada passed a law in December to set up an independent commission to replace ministerial reviews of suspected wrongful convictions, called the Miscarriage of Justice Review Commission. The law that created it was named after David and Joyce Milgaard. David spent 23 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit and was exonerated in 1997.

McLellan said the commission is based in Winnipeg with a full-time permanent commissioner. The part-time commissioners will be appointed before Christmas, he said.