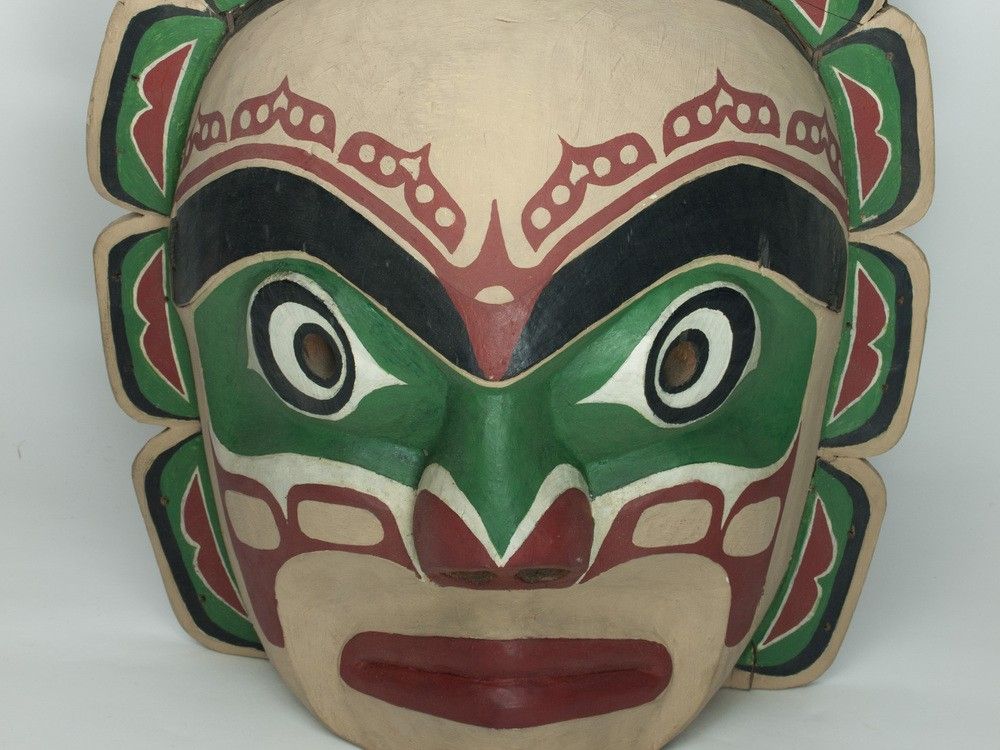

In 1957, a carved red cedar mask known as the “King of the Underworld” was sold, given a catalogue number, labelled and placed in storage at the Museum of Vancouver.

The masks’s previous life of dancing, ceremony and record-keeping in Gwa’yi village was over.

The Gwa’yi community, nestled in a glacial fjord on the central coast of B.C., also known as Kingcome and home of the Dzawada’enuxw people, had existed since de-glaciation about 12,000 years ago, but dwindled under colonial rule.

Like the King of the Underworld, many of its members were removed, given new names, and sent to residential schools and urban areas.

For the community, the recent homecoming of the King of the Underworld mask wasn’t just the return of an object, or an artifact that represented something long past.

This was the return of their future.

“It was the return of knowing,” said Marianne Nicolson, an artist and member of the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations.

Nicolson grew up watching the painful process of her community’s population decline, and wondering how to remedy it as she pursued her education in visual arts, as well as a PhD in linguistics and anthropology in Victoria.

Practical current challenges for families include not having a secondary school in the village, while historic challenges for the region include colonial policies of residential schools, land appropriation, and environmental degradation caused by open-net salmon farming, something the community successfully challenged in court .

“We were down to 65 (members) as recently as a few years ago,” said Nicolson. “I was afraid we were going to lose the community.”

So Nicolson began working with the local Nunwakola Cultural Society to take people from the community to faraway museums where parts of their culture had been stored away.

On a visit to the Museum of Vancouver in 2024, they asked to see masks. That is when they found the King of the Underworld.

The mask was old on its underside, said Nicolson, but looked like it had been freshly painted, possibly to spruce it up for sale to the museum or a collector.

Then she noticed something else.

A letter attached to it, dated April 16, 1957, described it as “an old mask that represents ‘the King of the Underworld.’ It belonged to my father, and I am not certain how old it is.”

The letter had been written by Nicolson’s mother, on behalf of Charles E. Willie, her grandfather.

Nicolson was not looking at an artifact. She was looking at a part of her family.

“It was incredibly personal,” said Nicolson. “When my grandmother died, my grandfather had all these children, and my grandfather was struggling to feed them,” said Nicolson. “He had to sell the mask to support his family.”

For Sharon Fortney, senior curator of Indigenous collections, engagement and repatriation at the Museum of Vancouver, this was an opportunity to do work that matters.

“Our mandate has changed,” said Fortney. “The mandate used to be ‘bringing the world to Vancouver.’ Now it’s ‘telling the story of Vancouver,’ and there is not a strong need for us to hang on to these objects.”

Although the museum’s collections are owned by the city, operating funds haven’t increased in decades, she said.

“It’s been challenging for us to do the work as we no longer receive financial support from the city for repatriation,” said Fortney, something she attributes to “changes in the arts and culture funding in the city.”

Fortney estimates the museum has some 80,000 objects in its collection. About 30 per cent of those are from Indigenous cultures around the world. Some were donated, or bequeathed, and others acquired because of economic duress. Many, like the King of the Underworld, were never displayed to the public.

The museum repatriates approximately three to four items annually.

“We want to help do repair work and healing in these communities,” said Fortney.

The sale of a traditional mask wasn’t unusual for that time period, said Nicolson, but came about because of economic and social oppression.

In August 2024, she returned to the museum with a group of 12 from Kingcome to view the mask. Don Willie, her uncle, the son of Charles Willie, who had sold the mask to feed his family, joined them.

Don Willie shares the hereditary name Yakatlan’lis with his grandfather, and as such is the current living representation of Yakatlan’lis among the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw of the Kwakwaka’wakw, explained Nicolson. Don Willie was the rightful keeper of the mask.

The mask is far more than an art form. Masks such as the King of the Underworld are actually legal texts, said Nicolson, and are connected to families, with specific rights and responsibilities. “Without having a written law, they act as legal recognition of title and rights to land.”

She and her uncle requested the return of the mask from the City of Vancouver.

Fortney began the legal process of transferring ownership of the mask and submitted a rationale, which usually includes the time period, how it was acquired — and whether it was under duress, as this one was — and explaining why it is not ethically supposed to be with the museum or is needed for cultural renewal or cultural survival.

The mask was packed by a conservator in a specially made box, and secured for its journey home over land and water. Nicolson picked up the box herself, drove to the float plane, flew to Campbell River and delivered it to her uncle’s house.

Don Willie planned a potlatch for May 2025 “to dance the mask in its home community,” said Nicolson.

Through anthropological records that held stories told by her ancestors, Nicolson learned the mask was connected to the story of the undersea kingdom.

As word spread of the mask’s return, William Wasden, a singer and composer who is Waxawidi of the ‘Namgis Nation of the Kwakwaka’wakw, reached out to say a song had come to him. He offered to choreograph a dance.

Boats were arranged for members of various communities to come to the village.

Kingcome’s population tripled overnight. Young people were invited to learn the dance, which expressed the community’s relationship to the sea.

Local teenagers became otters and seals and sea lions.

“They wanted to be there. They wanted to be a part of it,” said Nicolson.

“These were my nieces and nephews. My cousin, their children. All our children. Not on their phones. Not at home on their computers. They were in the Bighouse in Kingcome doing what we have done for thousands of years,” said Nicolson.

On the day the dance was presented to the community at a potlatch, the final dancer who emerged wore the mask of the King of the Underworld.

From her seat, Nicolson wasn’t viewing a thing of the past. “I thought, this is our future.”

“Our young people, performing and dancing. Dancing all the creatures of the undersea. At the very end, the King of the Undersea came through the entrance and carried my grandfather’s talking stick around the room, almost blessing it, and then they all left the floor and went out in front of the house, and then they came back in and took their masks off.”

In a letter thanking Fortney, Nicolson wrote, “For me and every one of the almost 300 witnesses, it was as if we were seeing our future on the floor filled with hope and return. Truly supernatural.”