In 1968 five friends, Yvon Chouinard, Doug Tompkins, Lito Tejada-Flores, Dick Dorworth and Chris Jones, drove a 1965 Ford Econoline van from California to Patagonia where they made the third ascent of Fitz Roy. The trip took nearly six months, with two of them on Fitz Roy, and 30 days spent in two different ice caves on the mountain. At one point they spent 15 consecutive days living in the highest one. The Patagonia winds made movement impossible.

The idea itself began almost casually. One hot morning in Ventura, California, Doug Tompkins was visiting Yvon Chouinard to surf when the talk turned to colder places. Slides of Patagonia, shown earlier by Argentine climber José Luis Fonrouge, lingered in their minds. As Tompkins later wrote, “One needs only to see a single mediocre color slide of the Fitz Roy massif to want to go there.” Chouinard mentioned the first ascent of Fitz Roy by the French in 1952 and recalled that Lionel Terray had called it “his hardest and finest climb.” By the end of the morning, plans were already forming.

They decided to leave in mid-July, travel slowly, and arrive in Patagonia for spring. More than reaching a summit, they wanted to rethink the very nature of an expedition. “Finger bells and chanting ‘Om’ would not be enough,” Tompkins observed. Preparation would come instead through surfing, skiing, driving, and eating well. They would approach Fitz Roy by land, surfing the west coast of Central and South America, skiing in Chile, and continuing south. For six months they intended to “hog fun.” By nightfall, “plans were piled on plans, fantasy on fantasy,” and to justify the indulgence they decided to make a film of the entire journey and “pass it off as a business venture.”

By July 12 they were underway. The team gathered gradually, with Dorworth joining as a veteran ski racer and speed record holder, Chris Jones planning to meet them later, and Tejada-Flores committing to document the trip on film. After months on the road, Bariloche offered a brief sense of comfort. Tompkins likened it to the Jackson Hole of Argentina, complete with mountains, lakes, and “superior steak dinners.” They adopted a strict steak diet, knowing it would not last.

Their first view of Fitz Roy came at sundown after months of travel. It was overwhelming. “We weren’t prepared for it,” Tompkins wrote. “We hadn’t known it would be like this! So big, so beautiful! So scary!” From sixty miles away the massif dominated the plain, with a glacier of “Himalayan” scale spilling into Lago Viedma. The effect was deeply unsettling. Tompkins described “a strong fear, a sense of losing confidence,” similar to arriving in Yosemite and suddenly seeing El Capitan. Nervous laughter followed, and conversation drifted briefly toward smaller objectives, but the truth was unavoidable. Fitz Roy was the mountain. “The script, however, was written the moment we first saw the range.”

What followed was a prolonged confrontation with Patagonian reality. Approaching from the east, as the French had in 1952, required full expedition tactics, a series of camps, and long stretches of waiting. They found what they had come for: “glaciers, couloirs, ice caves, the Total Alpine Experience!” Storms dictated everything. Eight days of bad weather forced retreats. Later, fifteen days trapped in an ice cave tested their morale. “Fifteen days in an ice cave without books or cards can wear heavy on the minds of even the most stable Funhogs,” Tompkins noted. Food ran out. Confidence thinned. Even after resupplying, the storms returned, and despite weeks of effort they knew they were “really not much further along than the first day we had seen the peaks.”

Then, without warning, the weather broke.

Leaving the Cado Cave at 2:30 a.m., they climbed fast. The granite proved exceptional, “rough surfaced with fantastic cracks,” and the team moved efficiently despite the cold and wind. Late in the day, waiting near the top, Tompkins understood that the long ordeal was ending. “I knew that we were going to finish the banana split that evening.”

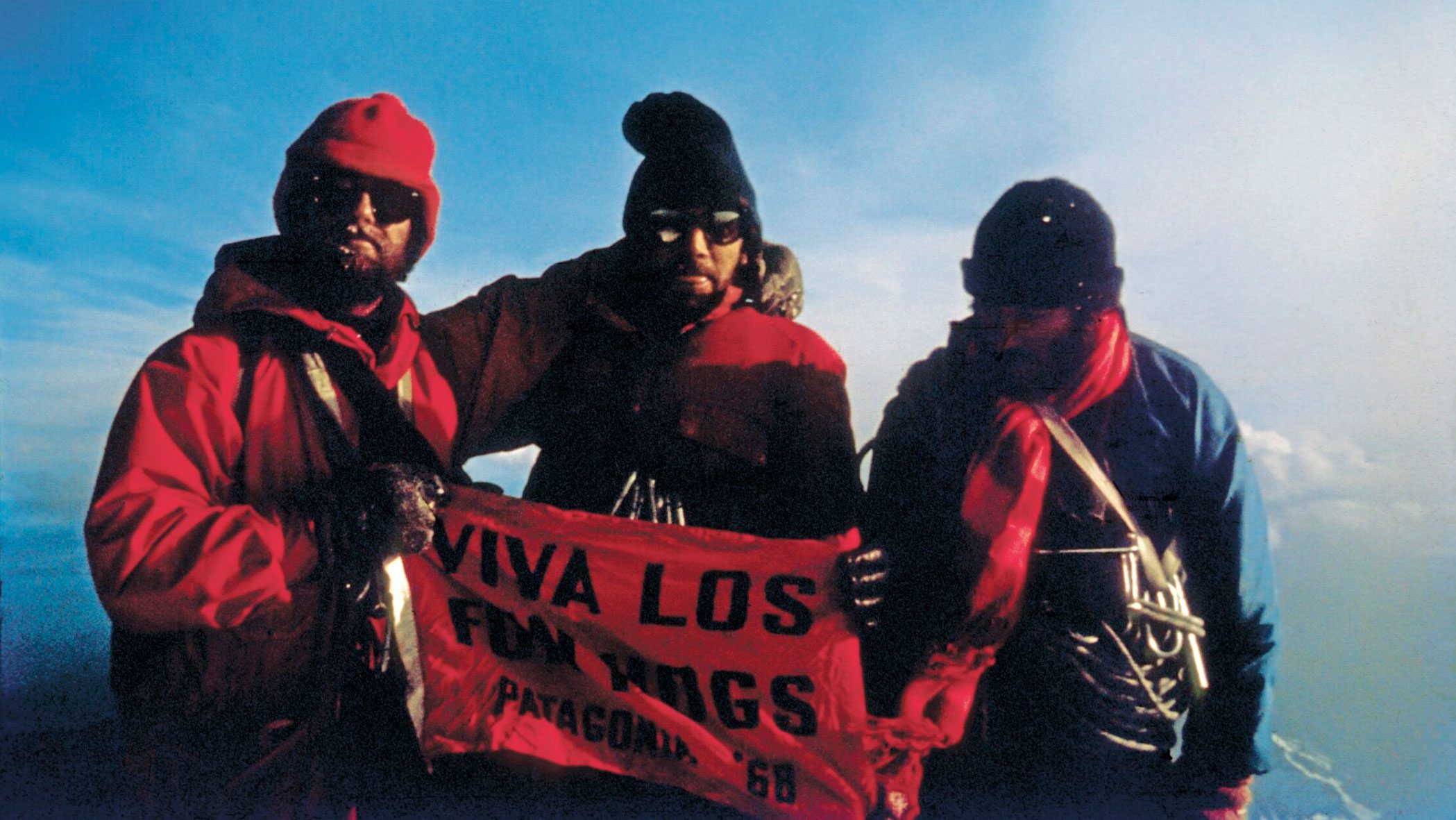

All five reached the summit at eight p.m. Cerro Torre lay below them, still wrapped in cloud and menace. After only minutes on top, they descended into rising wind, bivouacking miserably before reaching the ice cave the following morning. The climb, and the film, were complete. “The lines of the script had been spoken correctly.”

In the days that followed, as they dismantled camps and returned to the valley, the tension lingered. They rationed food they no longer needed and still woke early to check the weather. But summer had arrived. Green grass, birds, and running water marked their return. On Christmas Day, they hauled their remaining gear out under crushing loads, each carrying packs that weighed close to 100 pounds. What were they doing, Tompkins later asked, carrying such weight on Christmas Day? As they staggered back toward the van, they looked once more at “Old Fitz,” no longer an abstraction or a threat, but something known and familiar.

Tompkins said they were “just five tired Californian Funhogs finishing up the trip of trips,” smiling with “mustaches full of ice cream,” saying to one another, “I believe we’ve done it! I do believe we have!”

Mountain of Storms

The climbers filmed their exploits on a 16 mm Bolex camera and put their footage into a film called Mountain of Storms that was released the following year. From Ventura to a first ascent on Cerro Fitz Roy, with a stop for sand skiing and other adventures, the film was one of the first adventure documentaries ever made.

Mountain of Storms served as the mythological origin story behind the Patagonia name and philosophy, and informed a founding principle that would come to dominate the climbers’ lives for the next five decades: what’s important isn’t what you accomplished, it’s how you got there.

Sources: American Alpine Journal; Climbing Fitz Roy, 1968 by Yvon Chouinard et al.; Alpinist magazine.

The post Climbers Spent 30 Days in Snow Caves to Summit Fitz Roy appeared first on Gripped Magazine.