Earlier this week, I had a great chat with AI journalist Karen Hao about her new book, Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAI. (Which, by the way, looks like the book is killing it out there, congrats Karen, it’s getting lots of coverage and ticking up the sales charts; that’s what you call the Blood in the Machine bump.) As such, key points from her examination of the recent history of the AI industry have been on my mind, as OpenAI, Google and Microsoft made grand new announcements about their imagined AI-monopolized futures.

OpenAI announced it was teaming up with Jony Ive, the world famous designer behind the Mac refresh of the 90s, the iPod, and the iPhone. In a $5.6 billion deal, OpenAI is acquiring LoveFrom, Ive’s design studio, and Altman and Ive revealed that they’ve been building an AI device of some kind. Ive says, naturally, that it’s shaping up to be the biggest thing he’s ever done.

This after OpenAI has announced, in quick succession, that it’s pursuing an AI social media network, more work automation products, and AI for online shopping.

Meanwhile, Google and Microsoft both had their big product demo events—I/O for Google, Build for Microsoft—which featured a flood of AI services and products in different stages of development, from always-on AI agents that view the world from your smartphone camera lens to more Google Overview in more languages around the world to autonomous coding agents. AI, everywhere, all of the time; each of these tech giants—and Meta, too, as well as Anthropic—are driving to be the one-stop shop for consumer AI. One way to think about this is that the tech giants are using AI to try to entrench their monopolies, and to try to prevent OpenAI (or Anthropic) from building their own, which they very much want to do.

«A quick note: BLOOD IN THE MACHINE IS 100% READER SUPPORTED. I cannot do this work without my wonderful paid subscribers, who make all of this possible. I keep approximately 97% of my work unpaywalled, and it’s thanks to those supporters I can do that. You are the best. You are the reason I can pay rent, pay for summer camp for the kids, do a close read of a very long book to interview its author, spend a week reporting on the effort to ban states from making AI laws, and so forth. Please consider upgrading to paid if you can, for the cost of a nice coffee a month. This human thanks you—hammers up./»

In her book, Hao details how Altman’s two key mentors, the eminent VCs Paul Graham and Peter Thiel, sold their mentee on the ethos of growth-at-all-costs, and that startups should “aim for monopoly.” ”Competition is for losers” as Thiel famously put it. Hao also highlights a 2013 blog post from Altman, who muses “the most successful founders do not set out to create companies. They are on a mission to create something closer to a religion, and at some point it turns out that forming a company is the easiest way to do so.” Elsewhere, Altman talks admiringly of Napoleon, and his efforts to create and expand empire.

The unifying theme is Altman’s admiration for sheer ambition and unabashed megalomania. Using the quasi-religious trappings of AGI, or “artificial general intelligence,” software that can replace most working humans, as his chief product goal, Altman is pursuing relentless expansion in the mode of Amazon, Meta, and the other tech giants before it, around the strength of a popular product, ChatGPT. ‘Empire-building’ is a good critical articulation of what OpenAI and the other companies are trying to do with AI—given that it surfaces the exploited labor and environmental tolls necessary to make it possible—and “creating something closer to a religion” is a good description of how they are trying to do it. But “aiming for monopoly” is how all of this is being processed in the boardrooms.

“Aim for monopoly” neatly sums up OpenAI’s business strategy, much like “scale” summed up its approach to building better LLMs. It’s why DeepSeek, which built a competitive AI model for much cheaper, didn’t ruffle Altman’s feathers at all, even as news that such a model was possible briefly scrambled the markets. Altman has known from the start that the technology or even the product is ultimately ancillary to the power of the story. It’s the power of narrative, and of political standing, that justifies more investment, more partnerships, more public buy-in—and a shot at uprooting consumers used to certain tech platforms while providing them with what are in all functionality, often relatively similar services. (Information retrieval, software automation, digital socializing.)

Perhaps this has been obvious for a while now, but it’s what a lot of folks—myself included—sometimes get wrong about “AI.” It’s not a race to have the best technology, though all the companies surely want to do that, but more a race to become “The AI Company.” To become the first thing consumers think of when they hear “AI.”

This is why I think Altman and OpenAI execs no longer lose much sleep over the “moat” question; i.e., whether a competitor has a technological advantage, potentially resulting in its chatbot product being marginally better than ChatGPT’s. It’s because “AI,” which has never really been as much a technology as a concept, a marketing term, a loose description of a future-tinged idea about automation, is now even less than all that. It’s a commodity, a product category, a line of business, and naturally, all of these companies want to monopolize it.

The leadership of the established tech giants know that “AI” is a means of describing a new way consumers might want to search for information, and thus compete with their search products, or socialize digitally, and thus compete with their social media networks, or automate work tasks, and thus compete with their enterprise software offerings. This is the real reason they have gone so fully, and often embarrassingly, all-in on AI. (See this profile of Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, in which he says he doesn’t listen to podcasts but downloads them onto chatbots so he can ask questions about them. Very cool.) I’m sure they are excited by the technology, too, but the real threat has always been that a company like OpenAI can come along and undermine their key offerings with a better story about the future, with a flashier if less reliable product.

OpenAI meanwhile, is using its head start, self-curated mythology, and prime positioning in the broader AI story to aim for the heart of the sun and establish an AI monopoly at any costs. It wants to colonize the very public conception of AI, and knows that it has the best chance of doing so.

Where some people look at OpenAI’s latest announcements and see a rapidly advancing technology, I see a company desperate to plant its flag on any possible surface that might feasibly become an “AI” product or service. Part of this, as has noted in the link above, is a comms strategy—OpenAI has rather adeptly released a drip of AI announcements to keep the press and potential investors on the hook—and part of this is efforts of varying degrees of sincerity to attempt conquest in a a market segment, any market segment. The latest is some kind of AI-first device that will change everything.

And look, maybe I’m just disposed to be critical of all this stuff now. But to me it seems less revolutionary, than, I don’t know, desperate? For one thing, Altman is just *saying shit* now. He describes Ive’s company, with apparent earnestness, as “the densest collection of talent I think that I’ve ever heard of in one place and probably has ever existed in the world.” OK Sam. (You can see even Jony Ive struggle not to cringe as Sam rattles off those lines. In fact, I challenge you to watch this whole thing, it is borderline unbearable, and I hope that Francis Ford Coppola made enough of a location fee from letting them film in his wine bar Zoetrope to get a head start on Megapolis II.)

For another, let’s take a quick spin through the kinds of products that Altman and OpenAI has announced over the last months:

-A search engine

-A social network

-A web-based coding tool

-Online shopping

-A device designed by the maker of the iPhone

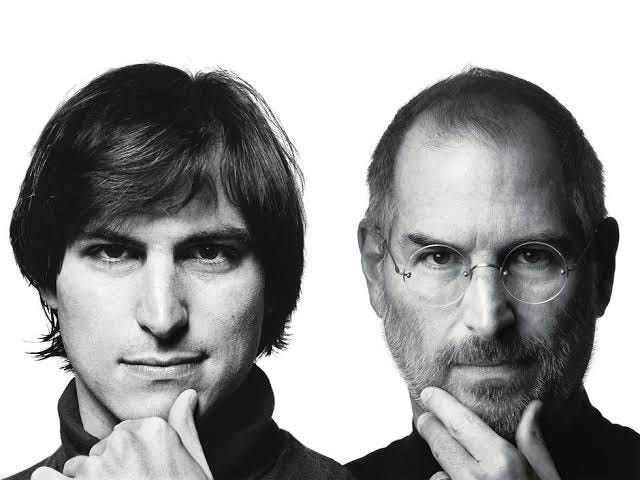

This is on top of previous efforts like an AI app store and workplace productivity software. In other words, it sure looks a lot like OpenAI is attempting to build a company that is all but indistinguishable from the other tech giants, just, you know, with AI. Just look at that picture above that OpenAI released with the Ive announcement—if there is a less subtle way to try to say “I am the next Steve Jobs” then I am certainly not aware of it.

And let’s think again back to the earliest days of OpenAI—again detailed in Hao’s book, as well as my own AI Now report on OpenAI’s origins—when Altman used Elon Musk’s framing of the AI x-risk problem, and even his very language, to get him on board to start OpenAI in the first place. The DNA of tech titans past is all over Altman’s project, from the tactics of the same VCs that helped build Facebook, the clear design lifting/legacy-bolstering from Apple, the ideology of Elon Musk, and the grow-at-a-loss until you’re unstoppable approach of Amazon.

Note that I am not claiming that the LLMs and chatbots at the core of OpenAI’s project are not a novel technology with unique applications from consumer technologies of generations past. But that for all of Altman and OpenAI’s talk of bleeding edge technology that stands to upend the foundations of the world itself, the technology is taking root in some pretty familiar ways! It’s the battle tested, VC-led, Peter Thiel-endorsed, quest for monopoly that has governed the Silicon Valley mindset since at least the zero percent interest rate era. AI is a normal technology, as the computer scientists and writers Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor have explained. But in order to become the next normal tech giant, Sam Altman has to go to great lengths to act like it’s not. Yet ultimately, Altman’s OpenAI doesn’t want to birth an AI god so much as it wants to be Apple.

Of course, that ZIRP era is now over. OpenAI has attracted historic sums of investment. It’s throwing around billions to brand itself as the next Apple with no actual device in sight. It’s still not close to being profitable. A lot of these initiatives feel pretty flimsy, to me, and there’s a mad dash, rush-to-make-a-deal-with-the-Saudis, see what sticks kind of vibe to a lot of what OpenAI’s up to these days. So the question becomes: What happens if you aim for monopoly—on a scale that no tech company has attempted as fast before—and you miss?

THE AI-GENERATED WRITING CRISIS IS IN FULL SWING

This week, the internet savaged a freelance writer who generated a summer reading list with ChatGPT, along with the Chicago Tribune, which published the feature, without edits, as part of an insert in its print edition. The outrage is justified: This is a profound failure of the editorial process, yet another depressing hallmark of These Times—AI slop making it to print—and an abdication of journalistic ethics.

And YET. I hope we save some ire for the tech companies that have actually created the conditions that pushed this writer to do such an unadvised thing. 404 Media interviewed the man, who turned out to be a veteran freelancer who puts together work like this as a second job in an effort to scrape together a living. And you know what? I feel for this guy.

No writer should ever use AI, that’s my hardline stance, for any part of the writing process. Editors should not be accepting AI-generated work. But let’s at least acknowledge the extent that Google, Meta, and big tech have corroded the economy for writing and journalism—through, what a coincidence, their monopolization of platforms that facilitate digital content distribution in a process not unlike the one described above—and that AI companies are here to drive a stake through its heart.

AI-content generation has facilitated a bona fide race to the bottom, where writers are getting paid so little in a lot of cases the incentives to use AI to auto-generate some text must be immense. Hell, I remember back to my up-and-coming blogger days some fifteen years ago, where I was paid $12 an article by a large media corporation to “add value” to existing news stories—I had to write one an hour to make anything close to minimum wage. And I thought it was my big break!

Hold fast to your ethics, yes, and don’t use AI to do journalism or writing at all if you respect your craft—but let’s recognize that AI slop is often a systemic issue created by monopolistic tech platforms and direct our energies to resisting such a system, and not exclusively to hating on victims who become enablers.

MORE BLOODY STUFF

I have gotten so many great submissions to the AI Killed My Job inbox. I hope to start sharing them next week — if I haven’t gotten back to you yet, and you sent in a submission, expect to hear back soon! For now, I’ll share the art that my friend Koren Shadmi whipped up for the project.

The Majority Report edited my segment on the AI jobs crisis into a standalone bit, which is cool.

This week’s System Crash covers some of this ground and more, so for a deeper dive into bad AI, why teens are rejecting the internet wholesale, and Grok’s white genocide freakout, give it a listen.

Okay! That’s about it for now, thanks for reading everyone, have a nice long holiday weekend rest, if you can. I’m going camping, and I think I’m gonna lock my phone locked in my desk, touch grass, read a book about anything other than AI. The hammers will be waiting on Tuesday.

*Thanks to Mike Pearl for editing help with this post.