For the last two winters, American climbers Brette Harrington and Elliott Bernhagen have been scouting, bolting, and working the moves on a four-pitch cave route on the east coast of Sardinia. Now, after freeing Shadow Line (5.14a) on March 31, Harrington is finally stepping into the sun—and has a story to tell.

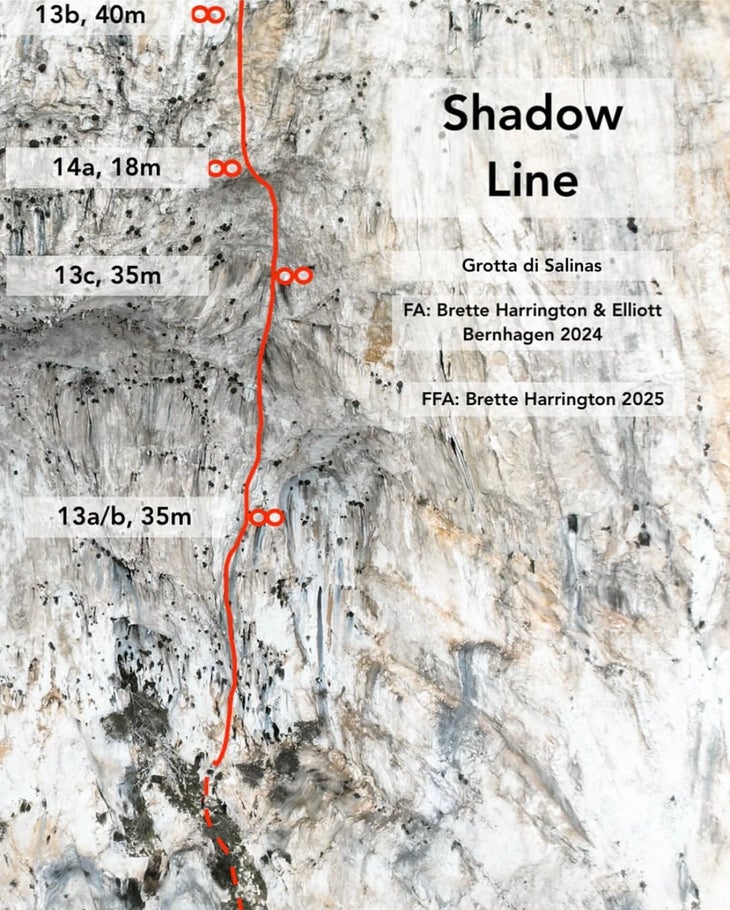

“It’s one of the most dramatic landscapes I could imagine. From afar, it was hard to tell if it would be possible for free climbing,” says Harrington, describing the cave, which bends over the Mediterranean to a near-horizontal angle for its crux pitch. Most of the pitches on Shadow Line are more than 45 degrees steep, at 5.13a/b, 5.13c, 5.14a, and 5.13b.

For many climbers, Sardinia brings to mind a relaxing vacation, but the challenge of establishing such a steep route forced Harrington and her partner, Elliott Bernhagen, to lean on their trad and alpine experience to find creative gear placements. After months of lassoing tufas, dodging falling blocks, and navigating runouts, the pair finished developing the line in December 2023. Harrington was determined to free it, but she only managed to send the first two pitches before running out of time on her trip. She returned to the route in February 2025.

“Pitch four was for sure going to go,” she admits, having climbed all those moves on a micro traxion, “but pitch three was really a huge question mark.” She spent 17 days working the crux pitch before sending it twice on the 18th day. “It’s the most time I’ve ever spent projecting a pitch.”

Not Your Average Beach Day

When Harrington and Bernhagen planned their 2022 visit to Sardinia, they wanted to try Aria (8a+/5.13c), a 10-pitch sport route on Punta Plumare, but they had concerns about corroded bolts, so they decided to scout the unclimbed coastline for a spot to put up their own line.

“If we’re going to put up a route, we’ve got to put it up on the most wild feature of this entire coastline,” Harrington told Bernhagen. For days, the duo took a boat and a drone out to the Mediterranean to fly a drone above the postcard-worthy Grotta di Salinas, which sits below the Punta di Salinas. In October 2023, they had a friend drop them off so they could scout an approach from the base. After scrambling 200 meters up through a jungle, cutting through thick vines with a machete, they found the scramble too loose to repeat every day. To avoid it, they bolted a rappel route to the side of the Grotta.

In Italy, a popular style for first ascents is to go ground-up and bolt each pitch on lead. First ascensionists would free climb, place a hook to drill a bolt, then remove the hook and keep free climbing—but if they fell, they’d have to start the pitch over again.

“I wanted to respect that,” Harrington says, “but I also wanted to put up a route in the cave.”

Placing hooks on a near-horizontal overhang just wouldn’t be possible. Instead, Bernhagen suggested that they might be able to use a rare piece of protection that Matt Maddaloni, a Canadian climber, invented in 2010: the “anticam.” The Y-shaped clamp was designed for protecting flakes, and when weighted, it would pinch between its teeth. However, when the pair tested it out on some tufas near the base of the climb, it immediately slipped out.

Her next solution was a makeshift lasso: throwing out her sling and letting it wrap around the tufa. “I could essentially jump though long passages of slow aid climbing more efficiently. These were delicate maneuvers because I didn’t want to break the tufas, and I also couldn’t tell how reliable my lassos were,” she says. Ultimately, Harrington was able to place enough bolts on lead by using a combination of delicate hooks, cams, and lassos. She says she bolted it with titanium expansion bolts to prevent corrosion by the water, and made them “pretty spaced” due to the clean falls.

“It’s not like a sport climb,” she laughs.

Harrington and Bernhagen dealt with a few enormous, dislodged flakes, especially while bolting the crux pitch. When Bernhagen was attempting to aid between the flakes, a ledge-sized one slid from the wall and landed on his chest before rolling off. “It was a pretty scary instance,” says Harrington. “We were really lucky it didn’t cut the rope.”

As a seasoned alpinist, Harrington is no stranger to committing moves and high-consequence falls. She first made her name in climbing by free soloing the 2,500-foot Chiaro di Luna (5.11a) in Saint Exupéry, Patagonia, 10 years ago. Since then, she’s put up several 3,000-foot rock and mixed routes across Alaska, Patagonia, Baffin Island, and the Canadian Rockies, including Sound of Silence (M8, WI5) on Mt. Fay and MA’s Vision (12c) on Torre Egger.

Recently, Harrington has been leaning into multi-pitch free climbing, redpointing both El Corazon (5.13b; 3000ft) on El Capitan in 2021 and Mezzogiorno del Fuoco (8b/5.13d; 7 pitches), another Sardinia classic, in 2022.

The Breakdown

Shadow Line follows a very subtle crack system, which sometimes opens up into gaping pockets and deep blue tufas. Harrington and Bernhagen originally climbed pitch one’s obvious crack from the base using mostly cams, but ended up bolting a different, tufa-heavy variation directly below the original anchors.

Pitch two (5.13c), according to Harrington, is a steep, 35-meter quest through a diverse mix of crimps, pockets, and other sculpted features. Near the top of the pitch, a pocket below a large blank section suggests a mandatory dyno, but Harrington solved it with what she calls a “really wild cross move.”

Although pitch three is the shortest, at 18 meters, it’s punishingly steep and consists of two V8 boulders stacked on top of each other with no rest between them. “The actual pitch takes me less than five minutes because I can’t stop moving,” says Harrington. “Even clipping is incredibly hard.” She suspects that the grade could be higher than 5.14a, and hopes to see another person climb it.

At the final pitch (5.13b), the climbing eases off, but not by much. An initial bouldering sequence leads to a no-hands rest before the grand finale: a two-bolt, 5.12c/d sequence on edges that even Harrington calls runout. When she finally sent the route on March 31—after warming up on pitch two, sending pitch three, and sending pitches one through three from the base—getting through the last pitch took maximum effort. “It was the highest number of hard pitches I had ever climbed in a day,” she says. “I had to fight to the very end.”

Harrington is now heading back to the U.S., but she intends to eventually return to the Grotta di Salinas to bolt another route next to Shadow Line. “There are a ton of really cool lines I’d like to try in that cave,” she says.

The post Brette Harrington’s Epic First Ascent in Sardinia appeared first on Climbing.