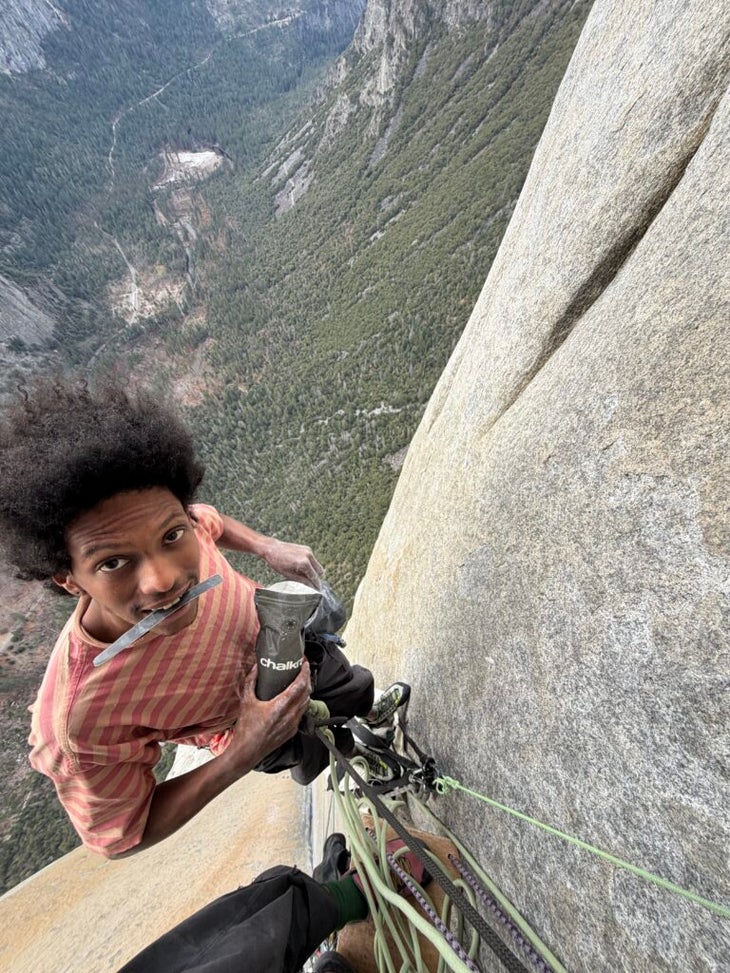

Tadros “Teddy” Eyob was high up on El Capitan when the infamous boulder problem finally slowed him down.

Eyob stared down the problem. A sequence of half-pad crimps, dime-edge holds, and a delicate thumb press stared back. The sweeping sea of granite up Free Rider (5.13a; 3,300ft) loomed larger than life in Eyob’s mind. But it didn’t feel impossible.

In the waning days of 2025, 30-year-old Eyob and his climbing partner, 21-year-old Rell Lennox, left the ground, climbing into a late November that felt more like summer than the tail end of fall. They cruised through Freeblast (5.11b), backtracked when their haul line snagged at the Hollow Flake, and climbed the Monster Offwidth during the hottest part of the day.

Eyob had flashed every pitch until the Boulder Problem. Now, he suspected, the fall was coming.

High above the Valley floor, Eyob was forced out of his rhythm, but he didn’t treat it as something to conquer. He spoke with animated glee as he recalled the crux pitch. “I like to work things out—to take my time and be strategic. I just need to understand the tech,” he explained of the delicate moves leading to the karate kick. So, when he fell again and again, it didn’t upset him.

Learning the intricate sequence had taken him the better part of the day. The pair slept on the Block Ledge that night. In the morning, Eyob tied back in, and cruised through the moves. The pitch went. And the climb, no longer a hypothetical, continued upward.

Eight days after leaving the ground, on November 30, Eyob topped out on his ground-up ascent of Free Rider, becoming the first Black climber to free climb El Capitan.

“ I didn’t really have any overwhelming sense of joy or anything like that,” said Eyob about the top out. “I [thought]: Oh, this could have been like 20 pitches longer, and I still would’ve been psyched.”

It was a milestone decades in the making, even if it wasn’t one he ever set out to chase.

How Teddy Eyob became a climber

Eyob first got into climbing almost by accident, while living in Vancouver in 2019. He was working as a bike mechanic at Mountain Equipment Company, a Canadian outdoor retailer, when he discovered the shop offered free climbing classes. At the time, he was dealing with insomnia, so he began going to a climbing gym with a friend.

Squamish, with its granite boulders and long routes, was only 45 minutes away. Eyob became a boulderer first. But eventually, he felt ready to expand. “Once you get around V10 in Squamish, things start getting really hard and thuggy,” he explained. So he started clipping bolts, then tried trad climbing. He found himself gravitating toward “super thin, short, hard trad routes” that felt bouldery and demanded precision, such as Trippett Out (5.13a) and The Free Grand (5.13a).

Big walls—El Capitan in particular—were never part of the plan. “I never really thought about it,” Eyob said. That is, until Lennox, a regular climbing partner in Squamish, asked if he wanted to partner up for Free Rider. His answer was instinctive: Sure, why not? How hard could it be? “I just wanted to go on an adventure with my buddy,” he said.

When Eyob learned he had become the first Black climber to free climb El Cap, it didn’t retroactively change the meaning of his ascent.

“I was honestly just kind of shocked… How has it taken this long?” Eyob said. As he flipped through the Yosemite guidebook, he noticed faces like his missing from its pages. “Every page,” he said, “it’s just white people.”

Why did the first free Black ascent of El Cap take so long?

The absence of people of color in the guidebooks of Yosemite and other climbing destinations is no accident. The Outdoor Industry Association estimates that only 9% of people who participate in climbing identify as Black or African American. For much of U.S. history, Black Americans were systematically denied access to land, safety, and mobility in the outdoors. Cultural theorist Caroyln Finney, author of Black Faces, White Spaces, pointed out that while John Muir was exploring the Sierras, the Black community was still reeling from policies like the California Land Claims Act in 1851, the Black Codes that followed the Civil War, and the Dawes Act of 1887.

Together, these laws helped define the outdoors as a space of exclusion long before it became a recreational ideal. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that segregation in national parks finally became illegal.

“People have this understanding that the natural world is equally accessible to all, but that is not the reality,” wrote Finney. “For Black individuals it can be a fraught terrain where we are at the mercy of someone else’s interpretation of our presence.”

In the decades since the Civil Rights Act, progress has come. Chelsea Griffie became the first Black person to aid climb El Capitan in 2001, topping out on Lurking Fear (5.7 C2; 2,000ft). Eddie Taylor has carved his own line of firsts, including becoming the first Black climber to free climb Moonlight Buttress in Zion in 2021 and aid climb the Nose (5.9 C2; 3,000ft) on El Cap in a day. Taylor also summitted Mount Everest with an all-Black team, Full Circle Everest, in 2022.

“It expands what feels possible,” Taylor said of Eyob’s historic achievement. “That’s the best part—moments like that naturally widen the sense of who belongs in these spaces, without needing to be a big statement.”

An open door still needs a guide

Eyob doesn’t frame climbing as an inherently exclusive sport, but he’s clear-eyed about access and culture. “Climbing feels like this thing that kind of gets passed down,” he said. Many first-generation immigrant families, he noted, aren’t spending weekends camping or driving to crags. “We moved here to work… we’re not going camping,” he said.

Even when the door is technically open, there isn’t someone leading you through it. “You pull up… and there’s like six white dudes with their shirts off, power grunting,” Eyob said bluntly. “It’s not a racist place, but it’s not the most welcoming vibe.”

Eyob has tried to widen that welcome. In Vancouver, he helped with community programs that took kids bouldering for free, teaching them how to move through the forest with confidence. “All you need to spark someone’s fire is to just feel safe,” he said. Eyob’s actions echo what outdoor journalist James Edward Mills, author of The Adventure Gap, has pointed out: Mentorship and invitation matter deeply in widening access.

Lennox said that energy is exactly why she chose Eyob as a partner. No stranger to El Capitan, 20-year-old Lennox became the youngest woman to rope-solo El Capitan via the Nose earlier this year.

The pair pre-hauled gear to the Heart Ledge, scouting out a few worrisome pitches before starting a ground push. Eyob led every crux pitch. His ability to try hard and his happy-go-lucky attitude made their eight days on the wall fly by, Lennox told Climbing, but there was something larger at stake as well. Their climb, she hoped, could be “the start of people of color climbing in the Valley and climbing on El Cap in a bigger group.”

With Free Rider barely in the rearview, Eyob is already looking forward. Chatting with Climbing as he packed for a trip to Chile, he plans to return to Yosemite in the spring with Lennox with a plethora of routes on his possible tick list.

Eyob is casually evangelical to anyone who dreams of climbing big, hard routes. “Climbing El Cap isn’t as hard and scary as it seems,” he said. “If you feel like you want to do something like that, you should go for it.”

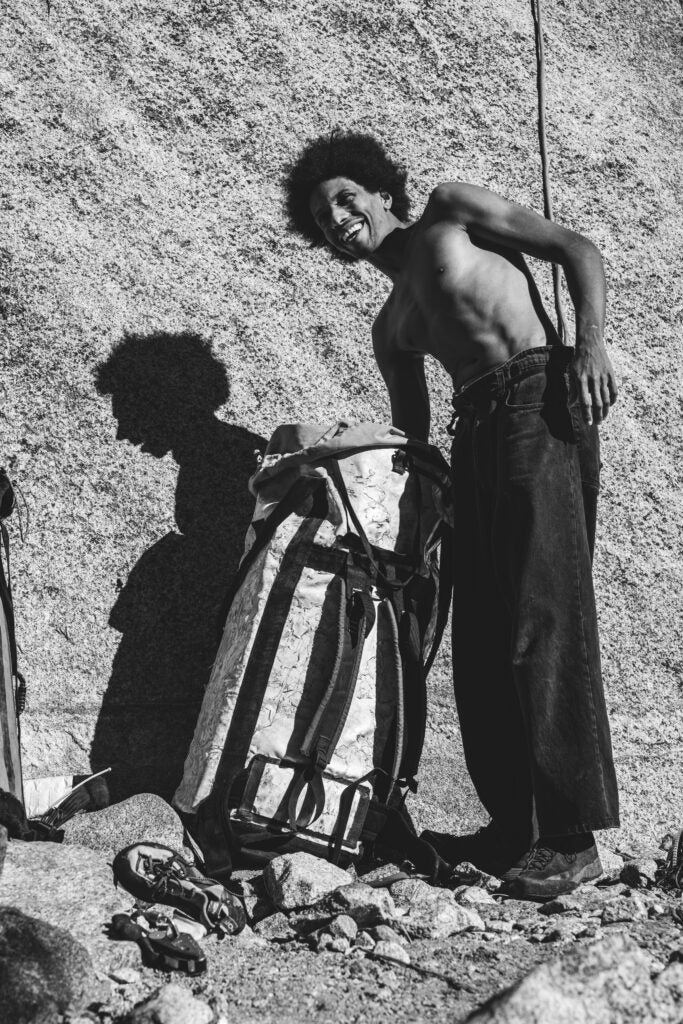

About the photographer: Felipe Tapia Nordenflycht is a Chilean outdoor and climbing photographer now based in the U.S. Originally from Chile’s Atacama Desert, he currently lives in his van, documenting high-stakes adventure sports and the environment. His work captures the raw intersection of human endurance and the natural world, inspiring conservation and diversity in outdoor spaces. Follow along @felipesh

The post Teddy Eyob Becomes First Black Climber to Free El Capitan appeared first on Climbing.