Warning: This story includes mentions of suicide and self-harm

Wayne Heinen lost his best friend on June 24.

“He was the greatest guy on earth,” said Heinen, who had known Rodney Wells since 1988 and spoke to Postmedia on behalf of the family.

When Wells, 61, was found dead next to his truck in his Lake Country backyard, the cause was readily apparent. He had taken his own life with a firearm. What torments the family isn’t just what happened, but why.

Wells had recently experienced an uncharacteristic battle with insomnia, and had been prescribed a cocktail of psychiatric medications. He was struggling to cope with side-effects of those medications, said Heinen.

After his death, the family requested an autopsy and toxicology tests.

“We needed to know what was in his system,” said Heinen.

The Kelowna coroner refused.

“I begged them. I even asked if I could pay for it,” said Heinen.

What the coroner said next shocked him.

“The coroner said she would lose her job if she did either one because the cause was already known,” said Heinen.

Studies show suicides can leave family members with complex grief, including post-traumatic stress disorder, higher levels of depression, and prolonged grief.

“Having an autopsy and toxicology report would help us understand and have closure,” said Heinen.

Heinen and the Wells family have joined the chorus of bereaved families critical of B.C.’s death investigation process.

The B.C. Coroners Service is responsible for investigating all unnatural, sudden and unexpected, unexplained or unattended deaths to determine the cause of death and other factors.

B.C.’s system has come under widespread criticism from experts who say the province is falling short. Only 3.2 per cent of deaths lead to an autopsy in B.C., according to Statistics Canada, the second-lowest in Canada. The rate was 7.2 per cent in 2010.

In 2022, Dr. Matthew Orde, a consulting forensic pathologist who practised in B.C. from 2013 to 2021, told Postmedia the B.C. Coroners Service was operating on a “bare bones model of death investigation” and had too few pathologists.

“We are in the dark because of some government rule,” said Heinen.

All Heinen knows is that between April and June 24, Wells was not himself.

A diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes in April had concerned Wells, who was a cancer survivor. He became anxious and had trouble sleeping.

“It flipped a switch in his brain,” said Heinen. “He had dropped 30 pounds in three months.”

Heinen advised Wells to seek a second opinion.

Wells went to a new doctor and his blood work showed that his blood sugar numbers were manageable, and nothing to worry about.

The new physician prescribed zopiclone, used for the short-term management of insomnia.

The side-effects of the drug bothered him. The physician advised him to stop cold turkey, said Heinen.

After two or three days, Wells called Heinen to say he hadn’t slept since stopping the meds.

“He felt like he was going crazy,” said Heinen.

What neither of them knew was that some studies show suddenly stopping zopiclone can cause anxiety, confusion and “ rebound insomnia ” and that Health Canada recommends getting medical help if users can’t sleep after stopping the drug.

Sleep disorders have been consistently shown to significantly increase the risk of suicide in population data .

“That was seven to 10 days before he died,” said Heinen, who now wonders whether stopping the medication so suddenly could have contributed to his friend’s worsening insomnia and his final catastrophic act.

“He wanted to get checked into the psych ward,” said Heinen. “He hadn’t slept in three days. He said he was going nuts.”

Contacted by Postmedia, the physician refused to comment, citing patient confidentiality.

On June 19, Heinen took Wells to Kelowna General Hospital to get emergency intervention.

The attending doctor told him there were no beds, but prescribed trazodone, an antidepressant that is often prescribed off-label for insomnia.

The doctor on duty asked Wells if he had considered suicide, to which Wells replied that the thought had crossed his mind, but he had not seriously considered it, according to Heinen, who was present for the discussion.

The doctor did not warn Wells or Heinen that trazodone has an FDA warning for increased suicide risk, said Heinen.

One study of U.S. veterans showed suicide risk increased by 61 per cent in those taking low-dose trazadone rather than other commonly prescribed insomnia medications.

In an email, the Interior Health authority said it wouldn’t comment on specific cases, citing patient privacy. But if a patient or family member has concerns with the care they received at Kelowna General Hospital, they are encouraged to contact the authority’s Patient Care Quality Office.

They left the hospital and filled the prescription. Heinen invited Wells to stay with the family.

Wells appeared to improve.

“The Sunday morning, he was mowing my lawn, fixing my furniture, he was almost back to normal,” said Heinen.

After a few days, Wells said he was ready to go home. On the last day of his life, he stopped at the bank, picked up some groceries, and attended a presentation at his granddaughter’s school.

Then, on June 24, he woke up at 3 a.m., went into his backyard, and took his own life. He did not leave a note.

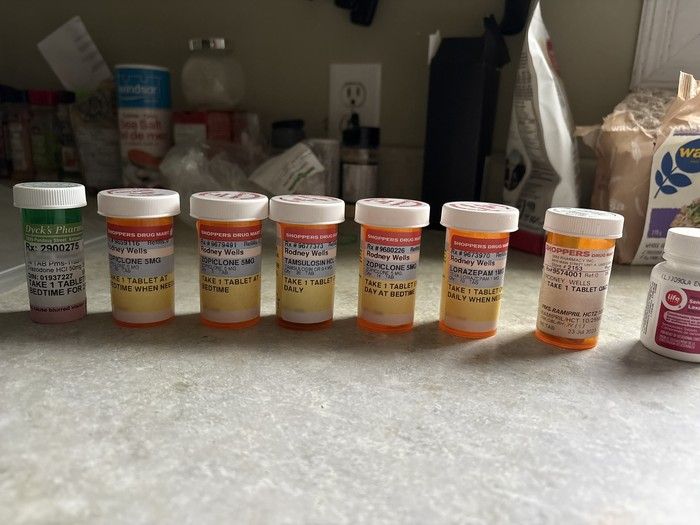

After Wells’ death, the family learned that in addition to zopiclone, Wells had also been prescribed lorazepam, an anti-anxiety medication, quetiapine, an antipsychotic, and mirtazaprine, an antidepressant. Elevated risk of self-harm has been reported for both quetiapine and mirtazaprine in medical journals.

“How many of those was he taking?” asked Heinen.

Four hundred people came to Wells’ celebration of life.

“We were best friends from the moment we met,” said Heinen. The Heinen family hired Wells as fabricator at their family business, B.C. Greenhouse Builders in Surrey, right after high school.

Wells had a toddler at the time. Wells and his son’s mother were on good terms co-parenting. In a particularly modern-family twist, Heinen married the mother of Wells’s son Devan, and the two men shared parenting responsibilities.

Both families moved later to the Okanagan, where they remained close-knit.

“People thought it was weird, but it wasn’t,” said Heinen. “He’s the godfather to my children. I’m the stepfather to his child.”

Now the family wants answers.

“Was he prescribed the wrong medications? Was it going cold turkey off the first medication that affected him?” asked Heinen, who was surprised to learn through this investigation that the medications prescribed to Wells carried a suicide risk.

There are larger questions related to public health, said Heinen. “If it was the medication, wouldn’t someone want to keep track of that? So it doesn’t happen to someone else?”

John Butt, a forensic pathologist and former chief medical examiner for the province of B.C., said the family deserves to know more.

Butt said making a determination of suicide is not enough.

“Suicide isn’t a cause of death. It’s a manner of death.”

To determine a medical cause of death, the coroner should examine not just what happened, but why, including the sequence of events leading to the death, said Butt.

Holly Tally, a spokesperson for the B.C. Coroners Service told Postmedia the investigation into Wells’s death remains open. When pressed for more, Tally said a final report setting out the coroner’s findings had not yet been completed.

Heinen said he and the family had heard nothing from the B.C. Coroners Service.

“My friend is dead. He’s been cremated. He’s in a box.”

The family would still like to know why.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, please call the crisis line at 1-800-SUICIDE, (1-800-784-2433).