News of another major mine inching closer to opening in B.C.’s northwest touched off a buzz in a region that has become more accustomed to absorbing job losses during a major downturn in the forestry sector.

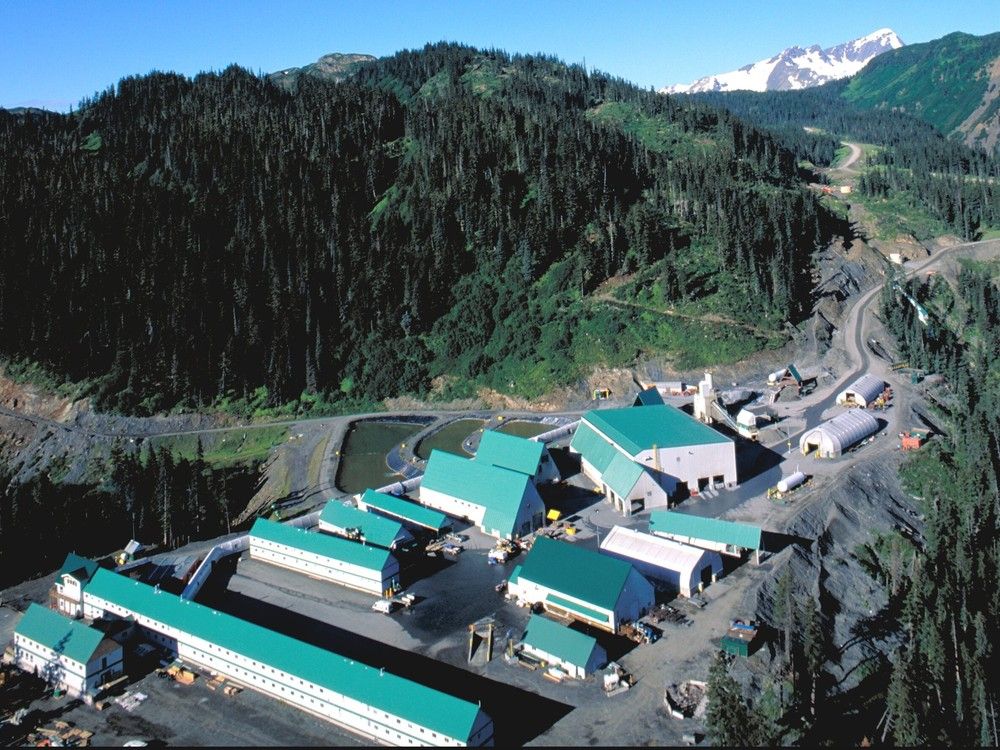

The mine proposal, Skeena Resources Ltd.’s project to reopen the mothballed Eskay Creek gold mine, would mean more than 1,000 construction jobs to convert the underground mine to open-pit operations, then some 770 permanent jobs to run the facility.

Eskay Creek environmental permit advances one of 24 major mine proposals across B.C.’s North identified by the Mining Association of B.C. as having the potential to become “the powerhouse” for the northern economy.

News about Eskay Creek was particularly meaningful in Terrace, the town of 13,000 some 690 kilometres north of Vancouver, once a traditional forestry town that has become an important hub for industrial development, including mining.

“The real win here is businesses are thriving in the community,” said Terrace Mayor Sean Bujtas, who greeted the word of the mine’s environmental approval as “exciting news.”

“There’s lots of traffic through the community, so that’s helpful to the local economy as well,” Bujtas added. “You’re getting all these people in the community, you get all these mines shopping and purchasing products in the communities, if it’s Smithers (or) Terrace, and that’s wonderful.”

Forestry, while it has been in a long period of decline, still dominates B.C.’s exports, said Bryan Yu, chief economist at Central 1 Credit Union.

And Yu said it’s difficult to make direct comparisons of the impact of mines, which typically export raw minerals, with sawmills, which are classified as value-added manufacturers. He added that mines take a long time to develop and it remains an open question whether some of them go ahead or not.

However, the Mining Association of B.C., has been on the road promoting its industry as the economic engine that will fill some of the gap being left by forestry’s decline.

The association, last week, published a revised edition of its economic impact study, which added four new advanced mining proposals to the list of 20 possible mines that could be built across northern B.C. that it released at the B.C. Natural Resources Forum in Prince George.

Its list includes projects that are proceeding, such as Centerra Gold Inc.’s expansion of the Mount Milligan mine northwest of Prince George, and those that are close to a yes-or-no decision, such as Eskay Creek, alongside others that are still more speculative.

Added up though, the list represents a total possible investment of $40 billion with $69 billion in economic activity over the coming decades.

B.C.’s main forest industry group, the Council of Forest Industries, has counted 21 permanent or indefinite sawmill closures since 2023 and 15,000 direct job losses in the sector since 2022.

And while development of mining projects on the list is likely to unfold over decades, association CEO Michael Goehring is confident “mining projects have the potential to offset or partially offset those job losses.”

Goehring said on average the association’s study estimated that a new, major mine in B.C.’s North would create some 1,500 direct jobs and 2,300 indirect jobs in its supply chain over an average mine life of 25 years.

“As a rough approximation, five or six new critical mineral mines could offset those recent direct job losses in the Northern Interior forest sector for 25 years or longer,” Goehring said. “That would be helpful for forest dependent communities.”

Vanderhoof, west of Prince George, has had experience with the decline of forestry and the rise of mining, and it’s a challenging transition, according to the town’s mayor, Kevin Moutray.

Vanderhoof lost 260 direct jobs at the end of 2024 when Canfor closed a sawmill in town, at the same time the mining firm Artemis Gold Inc. was building its Blackwater gold mine some 160 kilometres southwest of town, which “definitely softened the blow,” Moutray said.

“But it isn’t a silver bullet by any means,” Moutray added. “We have a number of people that have transitioned from millwork into working either at Artemis’s Blackwater or out at Mount Milligan, but it hasn’t been a large number.

“It’s something that we’ve tried to work on, how can we make that transition better for both the companies and the employees.”

Moutray said the nature of mine work, where employees typically travel in to mine camps for a week or two weeks at a time, is difficult for a lot of forestry workers who are used to going home every day.

“It’s a different lifestyle and some people have gone out there, tried it and it wasn’t for them,” he added.

Bujtas added that mines, while they’re major, wealth-generating industrial operations, also don’t generate property tax revenue for the small towns that are their service centres, like Terrace and Vanderhoof.

Both towns are part of a coalition of 21 small towns stretching from Vanderhoof to Haida Gwaii, called the Northwest B.C. Resource Benefits Alliance, which has successfully lobbied the province for limited pools of money to help cover infrastructure costs that Bujtas said are hard to accommodate with tax bases being depleted by forestry closures.

Then-premier John Horgan offered the alliance a $100 million planning grant in 2019, then $50 million the year after, which Bujtas said was a start, on an ad hoc basis.

In 2024, Bujtas, co-chairman of the benefits alliance, and Premier David Eby made a more consistent contribution of $50 million a year for five years, which gives Terrace $7 million and Vanderhoof $3.8 million a year to keep up with the infrastructure they need to keep pace with new the development needed for mining.

Butas added that the towns in the benefits alliance all owe their existence to industry, including mining, and “a lot of us are quite happy to” do their part in supporting what could be a bigger boom in B.C. mining.

“We’re just asking to not be left behind,” Bujtas said.