When a derelict former B.C. ferry burned while moored in the Fraser River last weekend, it was a reminder of the intractable problem of abandoned wrecks and washed-up boats of indeterminate ownership in waterways all over the province.

Mission Fire Rescue Service, the RCMP, Canadian Coast Guard and officials from the B.C. Ministry of Environment all responded to the blaze, which destroyed the already dilapidated former Queen of Sidney.

Environment Ministry spokesman David Karn said the boat was moored about 15 to 20 metres offshore and that the fire was contained to the ferry without causing pollution — other than the toxic smoke that led to a stay-indoors order for nearby Mission residents as the ferry smouldered in the early hours of May 3.

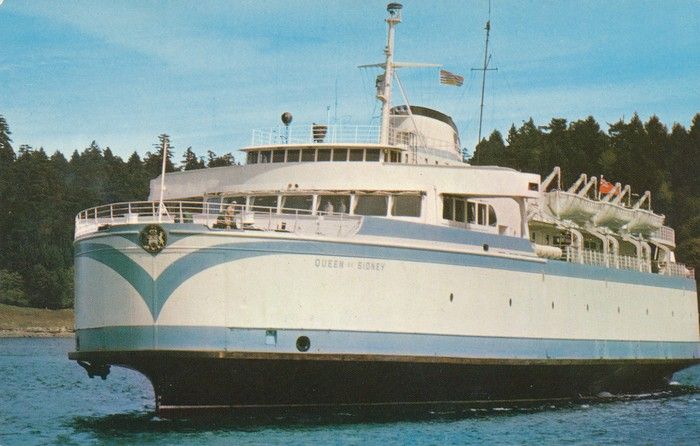

The Queen of Sidney was retired as a ferry 25 years ago and has been tied up in the Mission area in the two decades since. B.C. Ferries sold the decommissioned ship to a private owner in 2002 and no longer bears responsibility for the vessel.

But Ceilidh Marlow, a spokesperson for B.C. Ferries, said the boat, like dozens of other obsolete vessels, was languishing in something of a boat graveyard because recycling them is difficult and expensive.

Disposal is a major challenge: B.C. Ferries

“Responsibility for any vessel rests with the registered owner, including decisions related to moorage, upkeep and end-of-life disposal,” said Marlow in an email. Owners must make sure vessels are safely and legally disposed of, a process that is highly regulated to manage the environmental risks, she said.

“One of the major challenges in responsibly disposing of vessels — whether privately or publicly owned — is the lack of fully certified ship recycling facilities on the west coast,” said Marlow. “This is a growing issue that affects not only B.C. Ferries, but also other public agencies and private owners.”

Marlow said without local options, owners are left with the task of transporting them to other regions, often across the country, which is complex and costly. The lack of reliable local recyclers is a “known issue, and one we continue to flag as part of broader discussions on environmental stewardship and end-of-life vessel management,” she said.

With more ferry vessels due for retirement over the next decade, Marlow noted, the ferry service is making recycling and disposal a priority and has pushed for provincially recognized ship recycling infrastructure to be expanded locally.

Boat graveyard was a known nuisance

The ferry that burned is moored off a property on Cooper Avenue in Mission that is owned by Bob and Gerald Tapp. They have, over the years, collected a fleet that includes the ferry and several other dilapidated boats that were either bought or abandoned there by others.

The City of Mission has been trying for more than a decade to get federal and provincial agencies to deal with the potential environmental hazards of the boat graveyard, with little success.

“Given existing laws and the fact the (ferry) is not ‘abandoned,’ we are told there is not much that can be done,” said Mission chief administrative officer Mike Younie. The city tried to arrange a scrap metal deal with the Tapps several years ago, but it collapsed at the last minute, he said.

In 2012, the ferry and the other boats off Cooper Avenue were flagged as a concern during high water flows, but there was no plan to remove them — only to ensure they didn’t break away from moorage and create a safety hazard.

And indeed, the big boat would be dangerous if it became unmoored. The Queen of Sidney was a 102-metre, 3,127-tonne ship when in operation. It went into service between Tsawwassen and Swartz Bay in 1960 and was the first ferry to sail under B.C.’s new official flag.

Coast guard found ferry not a pollutant

Two years ago, the Canadian Coast Guard assessed the Queen of Sidney — perhaps ironically now christened the MV Bad Adventure — to determine whether it posed an environmental hazard.

At the time, it was found to be “a low risk to pollute under both the Canadian Shipping Act and the Wrecked Abandoned Hazardous Vessels Act, as there were no bulk pollutants on board,” said a coast guard spokesperson.

That may be largely because the ship had been stripped. Soon after it was retired as a ferry, it was bought by Art Klassen of Abbotsford, who paid $100,000 for it then hauled out copper wire, generators and other fittings to recoup the investment.

Now that it’s a burnt-out wreck, there are plans to “conduct a more thorough onboard assessment, with a specialized hazardous environment response team, in the near future,” said the coast guard.

But early assessments have shown it doesn’t appear to be causing pollution at the moment.

Fines are possible, but rarely imposed

The coast guard said it will board the vessel once the scene is fully cleared by the RCMP, who are investigating the cause of the fire. So far, there are no signs it was arson.

Any hazard-related costs, like cleanup, repairs or remediation done by the coast guard, are the responsibility of the owners under federal legislation. However, abandoning a vessel in Canadian waters only became illegal in 2019, and an inventory of abandoned and wrecked vessels wasn’t established until 2022.

That leaves the coast guard playing catchup, sifting through and trying to manage an inventory of over 2,000 boats reported wrecked or abandoned in Canadian waters. As of March 2024, 1,389 vessels remained on the list, while federal authorities had removed 791 others.

So far, the Canadian Coast Guard has levied only five fines since the Wrecked, Abandoned or Hazardous Vessel Act took effect.

Burned ferry is still being assessed

While municipal police and fire departments, provincial ministries and agencies like B.C. Ferries might be involved in trying to manage derelict boats, the wrecks are ultimately the responsibility of the federal government.

Under the act, owners “are liable for the costs of addressing hazardous vessels, and enforcement measures can be taken against them to ensure compliance,” said Transport Canada spokesperson Sau Sau Liu.

Liu said the response to the fire aboard the Queen of Sidney/Bad Adventure is being led so far by the RCMP and B.C. Ministry of Environment.

Depending on the outcome of the early assessments, Transport Canada might be called in to decide if further action is warranted under either the abandoned vessel act or the Canadian Navigable Waters Act , which restricts what kind of work can be done on, over or under navigable waters.

“Transport Canada reminds vessel owners they remain responsible for their vessels and any related costs under federal law,” said Liu.

Other derelict vessels on the list have languished in B.C. waters for decades, such as the MV Spudnik, a U.S. navy freighter removed from the Fraser River in 2020, and the cargo vessel Mini Fusion, a human smuggling ship formerly known as the MV Ocean Lady, which was removed from Desolation Sound in B.C. last year.

With files from Postmedia News, The Canadian Press, and research from Carolyn Soltau