On a recent weekday afternoon, Aline Mantuaneli and her husband, Adrian Murillo, brought their three-year-old son, Pietro, to the big-box Toys “R” Us store in Langley, situated on a prominent corner of the local Willowbrook Mall.

The bright aisles are a great place for Pietro to run a bit freely and check out the latest Transformers figurines he’s obsessed with.

“It’s safe inside,” Mantuaneli said. “We always come back, not always to buy.”

On this day, they were joined by a handful of young couples pushing strollers through the baby section, browsing the clothes and soft-touch goods. In another area, a few preteens checked out a bin of dinosaur masks based on the latest Jurassic World movie reboot that roar when their mouths open.

Mantuaneli has heard future plans for the Langley store — occupying a central location in a suburb burgeoning with young families — could include an indoor playground, which would be great, “because you can buy toys anywhere.”

But being able to buy toys anywhere is one the problems that Toys “R” Us Canada is grappling with as it works to reinvent itself in an increasingly fragmented world where digital games and entertainment are vying for parents’ attention and wallets alongside traditional Legos, blocks and Barbies.

Toys “R” Us, a shining beacon of childhood joy and a nostalgic throwback to how we all used to shop before e-commerce, is a last bastion of a venerable retail brand — a one-time “category killer” that helped to squash smaller independents during its rise in Canada’s retail scene.

While Toys “R” Us Canada may have survived the 2017 Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing that led to the closing of all the chain’s American stores, it’s now being squeezed by the same competitive forces that pushed its parent company into liquidation and reorganization.

The retail brand’s presence on Canada’s playtime landscape has shrunk considerably.

The Langley store is the only one left in B.C.’s Lower Mainland, following the closure of stores in Burnaby’s Metrotown mall and Richmond’s Landsdowne mall, as well as its prominent Vancouver store on West Broadway and even its original flagship store in Coquitlam.

In the past year, Toys “R” Us has also shuttered outlets in Kelowna and Kamloops, though its left open its store in Nanaimo’s Woodgrove Shopping Centre.

Countrywide, a recent Postmedia analysis found that the once-dominant chain of 103 stores has been reduced to just 40, with its owners looking for buyers for the real estate of 12 of those locations.

“I’m kind of not surprised they’re pulling back, that’s not a shocker,” said retail consultant David Gray of the firm DIG360.

The onslaught of digital games and entertainment, the arrival of e-commerce and the dominance of Amazon in that category, and the rise of discount retailers — particularly Walmart — all helped to saturate supply, according to Gray.

“From a supply point of view, choice became pretty commoditized, except where you had really special kinds of brands, like Lego,” Gray said. “There are more ways to get (toys) in the hands of consumers now, directly, than there would have been when Toys “R” Us was in its ascendancy.”

The heyday of big-box stores

Toys “R” Us Canada’s experience today is a far cry from when it arrived on the scene in 1984 as a disrupter in the country’s toy market, which, up until then, had consisted of independent stores, seasonal businesses within department stores and one major toy-store chain, Toys & Wheels.

“1984 was kind of the beginning of what became known as big-box retail,” Gray said. “Category killer (was) the term.”

These were massive destination stores that would carry everything in their particular niche category, Gray recalled. Think Best Buy for electronics and Home Depot for home improvements.

They “took out independents and took a bite out of department stores.”

“If you’re doing a timeline, I would say Toys “R” Us was the toy category killer and it just moved like a ‘Borg’ through that category,” Gray said.

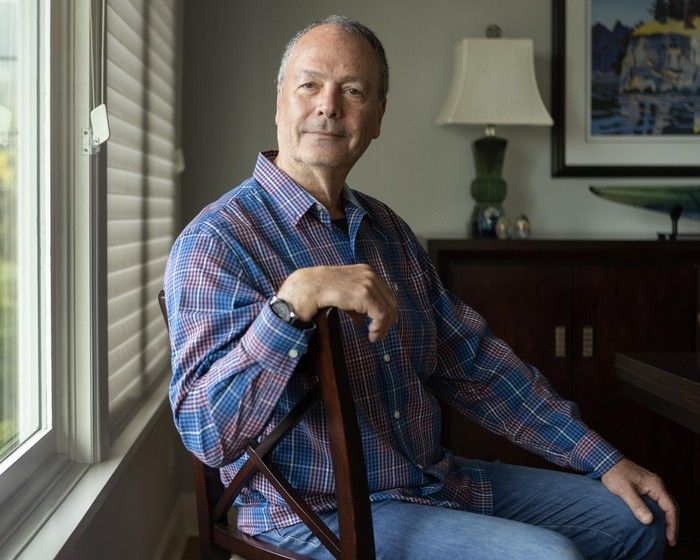

It didn’t happen overnight, though, recalls Reg Eland, who was co-president of Toys & Wheels.

The first stores that Toys “R” Us opened in Canada were set up as massive, 50,000-square-foot, stand alone destination stores, such as the outlet that opened in 1990 on Lougheed Highway in Coquitlam.

“They really didn’t affect us too much because they were big, big-box,” Eland said.

At the time, Toys & Wheels, which was started by Eland’s father in the late 1960s, had grown into its role as Canada’s top toy chain by following the expansion of shopping malls across B.C. and the West.

Eland said department stores that anchored shopping malls only really sold toys around Christmas, and mostly as loss-leaders with limited inventory.

So Toys & Wheels did great business selling the popular toys bigger stores had run out of from its 2,000-square-foot storefronts. And they were there year-round.

“It was great, it was a thriving business,” Eland said of the years before Toys “R” Us. “I’d go back to toy shows in Toronto or Montreal and New York and there’d be hundreds of different suppliers, so we could pick stuff that wasn’t in the big stores.”

That started changing in the early 1990s when grocery stores started vacating a lot of the malls that Toys & Wheels occupied, and Toys “R” Us starting taking over the 30,000-square-foot spaces they left behind.

Mall landlords “did everything they could” to get Toys “R” Us into those empty spaces, Eland said, which put them into head-to-head competition. Those same landlords, Eland said, wouldn’t let him out of his chain’s poorest-performing leases.

“Then, of course, when Walmart hit, that was it,” Eland added.

Discount retailers, which included Canada’s Zellers chain — which has since gone out of business — started opening toy sections as big as Eland’s stores. They had more buying power and were selling toys at loss-leader prices year-round.

“I could see every year the margins dropping and the costs going up,” Eland said. “We tried different things to combat Toys “R” Us, but there wasn’t much you could do.”

Toys & Wheels ran out of options at the end of Christmas 1994 and voluntarily entered receivership at the start of 1995 to wind down operations of its 78 stores. Some 800 people lost their jobs.

“We lasted longer than Woodward’s,” Eland said. “And a lot of big retailers went broke before us.”

Digital disruption

Toys “R” Us enjoyed market domination for many years but started to show stress in the early 2000s due to a cascading list of factors, according to Gray.

For one, the market for toys was starting to fragment with the arrival of video games and other digital toys.

“There’s a real kind of switching around and disruption in terms of what’s popular with kids,” Gray said. “A lot of it went digital and the whole digitization of toys and (video) games kind of took over.”

So, toy stores started losing teenage customers, who used to be drawn to train and car-racing sets, to electronics stores or specialty video game boutiques, Eland said.

“Future Shop carried (them) and they just gave them away at a 10 per cent markup, or something,” Eland said. “We can’t compete with that. And then the whole market shrank.”

The seeds of Toys “R” Us’s decline were perhaps already sowed at the same time they were expanding, according to observers who watched big-box retail reshape the shopping landscape in the early 1990s.

In a 1994 Vancouver Sun story, Cambridge Shopping Centres president Lorne Braithwaite, who watched as the “power centre” concept of free-standing, big box stores supplanted traditional shopping malls, already guessed that “big-box dominance can’t last forever.”

Even then, it was clear to Braithwaite that while some stores would persist, “the break-even point for those stores is very high, so if they make a mistake, it bleeds very quickly and it has to be fixed very quickly.”

Gray said for Toys “R” Us, “the cracks were forming part and parcel with Amazon,” which started to really cut into everyone’s retail sales, including the toy market.

Retail strategist Russel Whitehead added that Walmart has also really become an “everything” destination for consumers who have less time and fewer resources to buy toys in the first place.

“If they live close to a Walmart, for example, they can go to Walmart to get their groceries, get a few toys there at the same time,” said Whitehead, senior vice-president of planning and development for commercial realtor CBRE. “Maybe it’s not as big a selection as Toys “R” Us but it still offers most of what they may need.”

As Toys “R” Us locations face rising lease rates and operating costs, along with declining retail spending, “it’s kind of simple math,” Whitehead said.

What were once sustainable, 30,000-square-foot stores are only viable at maybe one-third their size.

The future

But the changing retail landscape doesn’t mean there is no longer any room for bricks-and-mortar toy stores, according to Gray.

He sees conditions as more conducive to specialty stores.

Whitehead added that shifting demographics — an aging population and shrinking fertility rates — are shaping a lot of decisions.

“It makes sense why Toys “R” Us has retained its Langley store location, Whitehead said. “Significant population growth going on out there. There will be the SkyTrain connection, it’s located close to that.

“Affordability (of residential real estate) is another driving factor pushing younger families to move out there.”

The store locations that Toys “R” Us are vacating, however, do pose a challenge for a strained retail market.

“That anchor space, that will be tricky,” Whitehead said.

Some locations will be ripe for redevelopment. The marquee West Broadway location in Vancouver under the historic BowMac sign, for instance, is within the City of Vancouver’s Broadway plan, which will likely see high-density mixed use development in its place.

However, Postmedia News reporters identified 39 Toys “R” Us stores that have closed in 2025 alone and “it’s hard to find another operator to fill that in,” Whitehead said.

With files from the Edmonton Journal and the Financial Post

The Last Toy Stores

Read our series about the changing landscape of toy retail

This story is the second instalment of The Last Toy Stores, a five-part series exploring toy retail in Canada as Toys “R” Us, the country’s largest chain, shrinks its footprint. The series was produced by the Financial Post Western Bureau, a partnership with the Edmonton Journal, Calgary Herald, Saskatoon StarPhoenix and Vancouver Sun.

Check back for more stories from this series.

Monday : A toy empire that has dominated Canada’s retail landscape for decades appears to be shrinking, with a new analysis showing Toys “R” Us now operates fewer than half of the locations it ran just four years ago — and even more are up for sale. Read this story now .

Today : ‘Category killer’: How Toys “R” Us disrupted the children’s retail industry, only to find itself disrupted by a range of market forces.

Wednesday : Who is the man who took over Toys “R” Us Canada, grew Sunrise Records from HMV’s ashes and bought other struggling retailers? Find this story at financialpost.com.

Thursday : Their love blossomed in a toy store. A look at how Toys “R” Us came to be a source of nostalgia, and even some life-long relationships, for generations of Canadians. Find this story at calgaryherald.com.

Friday : When Bob Siemens moved to small-town Saskatchewan with a vision to transform a sprawling historic building into a giant toy store, some people in his life thought he had lost his way, and possibly his mind. A look at the role of independents in retail. Find this story at thestarphoenix.com.