Greetings fellow bloodied machinists —

The fun never ends. Last week was marked by national security-threatening Signal chats and the socially mediated march of fascism; the broad daylight disappearing of students and state-produced content humiliating immigrants. This week, we’re dealing with all that *and* a haphazardly instigated global trade war that threatens to tank the US into recession—and which sure seems to have been hashed out by ChatGPT. That, of course, is the product offered by the company that, a few days earlier, closed the single largest private tech investment deal in history.

So in this newsletter, we’ll tackle

How we came to get AI-generated tariffs in the White House, and

How “AGI” helped enable those tariffs—and landed OpenAI a record-breaking $40 billion in investment this week.

Since the two are connected, let’s start with AI-generated tariffs. Buckle up, and I hope everyone’s hanging in there, and stocking up on imported goods and good takes.

How we got to AI-generated tariffs

I do find it darkly funny—look we have to laugh, right?—that we’ve spent the last month or so embroiled in another round of debate and speculation about whether super-intelligent AI is on our doorstep, and asking probing questions like “Will an AI emerge so powerful that it will utterly transform the world as we know it, throwing millions out of work, or worse??” only to see the White House use AI in a way that risks doing precisely that, but in a way that can only be described as super-dumb.

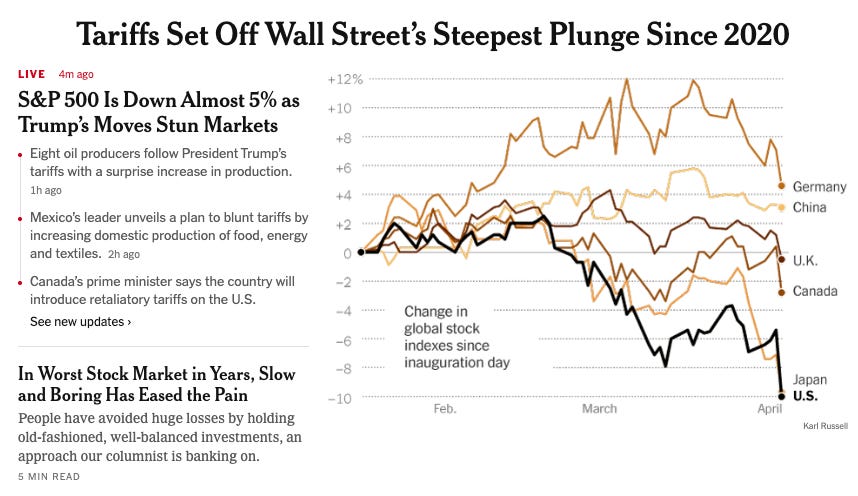

You may have seen the gist of this explained already, so I’ll keep the recap brief: Basically, when Trump announced the tariff rates at one of his typically meandering press conferences, analysts were pretty stunned by how large and punitive they were, and by the fact that the figures didn’t seem to make much sense. That is, until the finance journalist James Surowiecki figured out that the Trump admin hadn’t calculated tariff rates at all, as they said they had, and had instead just taken the US trade deficit with a given country and divided it by that country's exports to the US. This, as Surowiecki put it, is “extraordinary nonsense.”

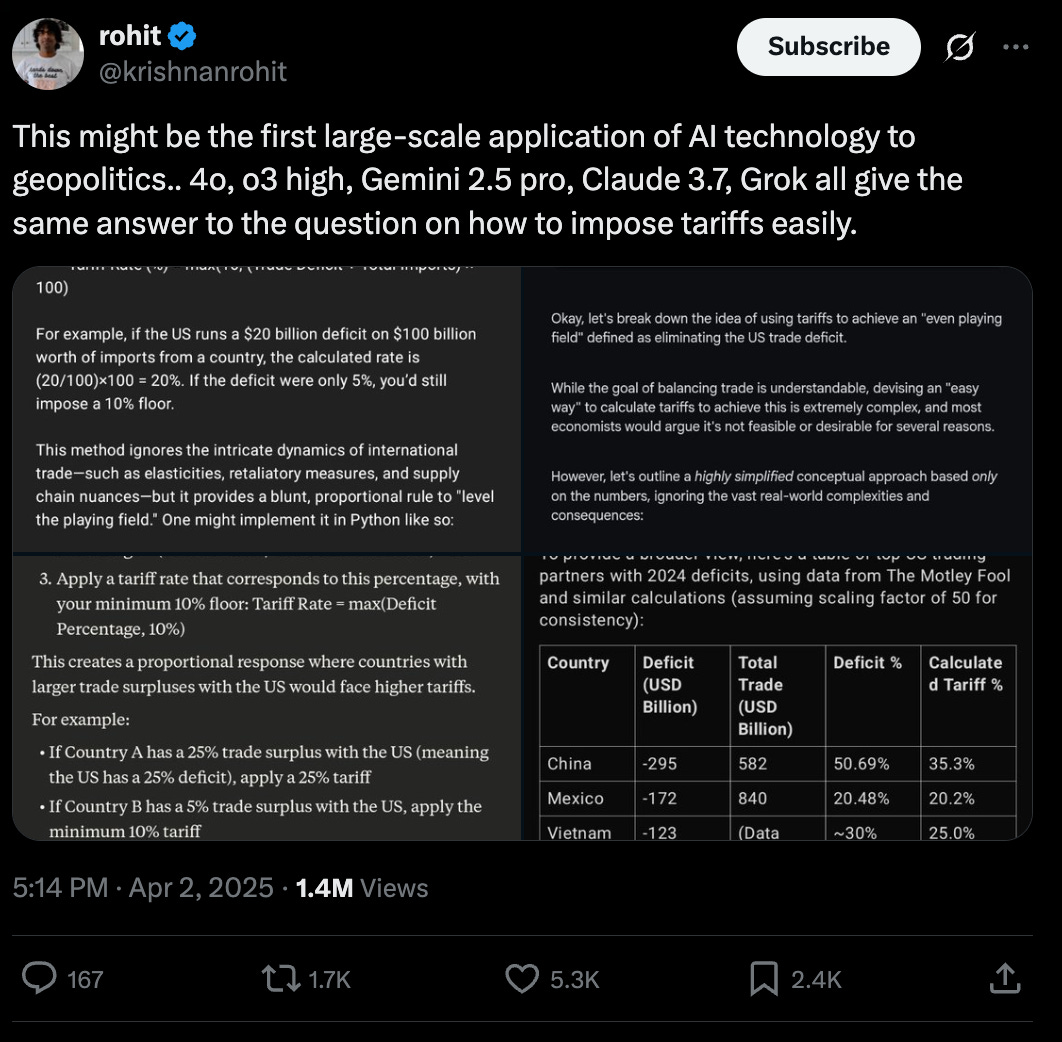

And how might the Trump administration have come to decide that this extraordinary nonsense was in fact a good way to craft global trade policy? Well, it looks like AI chatbots told them it was! The basic formula Surowiecki ID’d was, as the VC and AI advocate Krishnan Rohit and others pointed out, the very formula that every major AI chatbot suggested when asked “how to impose tariffs easily.”

Others, including yours truly, have replicated the results.

Now, the Trump administration will probably not admit to using a chatbot to create tariff policy that has sent markets tumbling in what are now the worst days of trading in years (the Dow is down 1,600 points at time of writing). But it more than fits the bill; the Trump administration, after all, is reckless, impatient, and high on American-made AI. And it would be tempting to answer the question of why Trump’s team turned to AI for such a momentous task with ‘because it was there’ or ‘because they could and they are lazy’ and leave it at that, even if that probably gets you most of the way there.

But there’s another factor, and it is related directly to OpenAI finalizing that massive infusion of cash earlier in the week: The AI industry has rather relentlessly been touting its products’ awesome power and capabilities for years, and, as we’ll see below, that promotion has been especially acute in recent months. If one of Elon’s DOGE lackeys was told to come up with tariff rates for Trump’s big Liberation Day announcement, he would probably consider the technology perfectly capable of calculating them. (Observers like point out that the equations and explanations the Trump admin shared as proof it did in fact calculate the rates seem quite rushed.) We’re a couple of years away from all-powerful AI systems! Surely AI can spit out some tariff rates.

This is actually a pretty great example of the kind of assumptions commercial AI systems encourage—they’re sold as ultra-powerful, or about to become so, and thus many users are prone to over-index on their capabilities. They encourage laziness, or “cognitive offloading” as researchers more diplomatically put it, and deter critical thinking (like the kind that might lead one to ask whether it is a good idea to impose tariffs on uninhabited islands). They’re adept at tasks that require ‘good enough’ output—say, producing marketing email copy, images for corporate power point slides, or tariff rates to be printed out in very small font on a poster board to be gestured at by a guy who really just wants to stand at a podium in front of the cameras and hear himself talk for an hour.

The bottom line is that the AI industry has created a permission structure for use cases like this one, with its “incredibly capable” AI systems, and AGI just on the horizon. (And what’s more, I’d take odds that the staffer or intern or DOGE employee or whoever did this may successfully be lobbying to keep his job right now on the grounds that well it was the AI that did this, not me! Because AI can also be used as an accountability sink!)

Look, I’m begging people to take this all-time example and look at the yawning gulf here—between the marketing promises of the always latent “all powerful AI that benefits all of humanity” and the reality of “White House intern uses ChatGPT to generate trade policy that might cause a global recession.” Predicted benefits, and proven harms, to paraphrase the scholar Dan McQuillan. We cannot blame this disaster on AI itself—it is, of course, also an enormous user error. But still: This is how AI is being used, in practice! This is what AI is delivering us, right now! It’s being used by the cruelest and laziest people—who may or may not actively want to crater the US economy in the hopes that it consolidates their power—to automate critical decision making.

As for how we arrived at this juncture, where so many are left to assume AI is imbued with some degree of super-intelligence, and with even more on the way, well that’s the subject of part II of this very newsletter.

Selling “AGI”

This week, OpenAI closed yet another titanic and oddly structured deal. On paper, the maker of ChatGPT is now more valuable than McDonalds, Chevron, or Samsung, despite evincing few to no signs that positive cash flow is anywhere on the horizon. So how do we account for an investment firm, even one as profligate as SoftBank, dumping a historic amount of cash into it? Well, let’s consider at least one significant ingredient at work here—the promise of the above-mentioned “AGI.”

Last month, there was a flareup in mainstream AGI discourse. Two New York Times columnists, Ezra Klein and Kevin Roose, each published pieces forecasting the imminent arrival of Artificial General Intelligence. “The Government Knows A.G.I. Is Coming,” read the headline of Klein’s March 4th piece, which inspired a round of online chatter, spurring folks like Matt Yglesias to chime in with agreement. Roose’s column, originally tilted “I’m Feeling the A.G.I.” was even more direct with its second: “Powerful AI is Coming. We’re Not Ready.” Takes were written, critics were chastised, the case for AGI advanced and argued over.

During the month that these columns were published, OpenAI was, per the Wall Street Journal, negotiating its latest—and largest—funding round, led by the notorious investment firm SoftBank. On March 31st, news broke that a $40 billion investment was finalized, and that OpenAI had closed the largest such deal in history.

The now $300 billion-valued OpenAI headlined its own official announcement of the investment “New funding to build towards AGI.”

The brief release notes that:

We’re excited to be working in partnership with SoftBank Group... Their support will help us continue building AI systems that drive scientific discovery, enable personalized education, enhance human creativity, and pave the way toward AGI that benefits all of humanity.

The promise of AGI, we can infer, is a leading reason why SoftBank was willing to invest historic sums in OpenAI—these releases serve as a confirmation of purpose to participating investors as well as a framing device for the press. As such, I’d love for us all to look at this timeline and interrogate the role that the construct of “AGI” plays in feeding the mythology of marketing and attracting investment for big AI firms.1

In his column, Roose talks about how widespread the belief that AGI is imminent is in Silicon Valley and around the Bay Area, how people talk about “feeling the AGI” at house parties—and I have experienced that too, in my trips to the Bay. But it’s still a radically industry-centric belief; even if it’s one not purely motivated by money or portfolio-boosting. Such trends, even manias, have gripped Silicon Valley plenty of times before. I can recall lots of Silicon Valley functions where folks were talking about crypto, or “Uber for X,” or social apps with similar zeal.

Would OpenAI have closed this deal with or without the renewed excitement about AGI in The New York Times? Who knows? Probably! This is the firm that invested $16 billion in WeWork, after all. But the added dash of AGI inevitability certainly didn’t hurt. More importantly, it was already in the air—and we should understand how this AGI mythology has to be continuously cultivated, updated and upgraded, so that it still commands meaning to the press, and more importantly, to potential investors.

I’ve been beating this drum for a while.2 Last year, while researching a report for the AI Now Institute about the generative AI industry’s business models—an undertaking that involved combing through OpenAI’s blog posts and press materials from its earliest days on—I noted each time the term ‘AGI’ surfaced, and in which context.

To quote from my own report:

Tracing the usage of the term “AGI” in OpenAI’s marketing materials, patterns emerge. The term is most often deployed at crucial junctures in the company’s fundraising history, or when it serves the company to remind the media of the stakes of its mission. OpenAI first made AGI a focus of official company business in 2018, when it released its charter, just after it announced Elon Musk’s departure; and again as it was negotiating investment from Microsoft and preparing to restructure as a for-profit company.

The pattern continued through the launch of ChatGPT, and continues today. In February, amid the negotiations with SoftBank, Sam Altman published a widely covered message—Roose cited it in his AGI column—that pronounced, “Our mission is to ensure that AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) benefits all of humanity… Systems that start to point to AGI* are coming into view.” Altman then lists three observations about modern AI, including this one:

The socioeconomic value of linearly increasing intelligence is super-exponential in nature. A consequence of this is that we see no reason for exponentially increasing investment to stop in the near future.

We’re used to overblown pronouncements from Altman and the AI sector, but this is a wildly audacious statement even by those standards. And I think it’s a finely crystallized example of why we should be suspicious of broader AGI claims. Here we have the CEO of the company at the vanguard of the AI industry, beginning his message by declaring that AGI is almost here, and the takeaway is literally and without exaggeration you should invest exponential sums in our company.

Even Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, OpenAI’s top competitor, has said that he’s “always thought of AGI as a marketing term.”

I’m not even saying that AI is “fake,” as Roose’s colleague Casey Newton might accuse me of—I also think it’s folly to argue that, myriad ethical questions about training data and resource usage aside, LLMs aren’t impressive in a lot of ways—I’m saying that there is a particular tactical approach these companies take, deploying “AGI” to woo investors and promote the power of commercial products in the press, and that it’s not new, but it’s still working. I’m saying we can discuss the promises and risks of these technologies without using a framework that pretty directly serves the industry’s interests. A $40 billion investment! In a company that’s losing $5 billion a year! Even if you are an AI aficionado that has to boggle the mind on some level. And, sure, it may be that investors may simply be that impressed with the technology, or that maybe they’ve even been treated to demos no one else has, or seen a secret business model that stands to ramp up OpenAI’s revenues starting first thing next year—but largely I think it’s blunter than all that: that the very concept of AGI has been rendered in such a way that it’s simply too enticing for large investors not to buy into.

In its charter, OpenAI defines AGI as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.”3 OpenAI has defined AGI that way since 2018. This promise, that OpenAI stands to automate all meaningful work, is the big one. That’s been the dream of industrialists for 200 years—a world without workers. What if OpenAI can do it? All those other investors seem to think it can, or at least has a shot at it, and the rest of the entire industry, from Google to Anthropic to Microsoft, is behaving like they can too. AGI has collapsed all other horizons in Silicon Valley around this one promise. That’s how you get $40 billion in a single funding round.

That’s how you get a world where more and more people buy into the idea that AI can do nearly anything, like automate handcrafted animation or replace federal workers with chatbots—or auto-generate national tariff policy on the fly. A world where we are promised AI systems so powerful and so radical that they risk throwing everything into chaos because we are not ready for their immense capability. But where in reality, they are used today to unthinkingly dictate crucial trade policy that tanks the global economy. The events of this week have at last made this point clear.

The true threat to the global economy and our social order is not super intelligent and powerful “AGI.” It is the thoughtless people in positions of power using the products sold by the companies who promise it.

That’s it for this week. Thanks as always for reading. And again, if you appreciate critical analysis of AI, Silicon Valley, and our tech oligarchy, consider becoming a paid supporter so I can keep doing it. Take care out there.

Notably, I’m not suggesting that Klein and Roose are intentionally helping to juice OpenAI’s valuation or anything like that. In fact, at the risk of having my AI critic card revoked, I’ll even say on record that I like Kevin, and as a former tech columnist myself, respect his columnistic craft—columnists are supposed to infuriate people, and what can I say, he’s got some good hooks. He also reads this newsletter, I believe, so: Hello Kevin! Have me on Hard Fork sometime so we can argue about all this. That said, I do vehemently disagree with his AI analysis (and crypto and web3 analysis even)—and that really good software automation does not portend AGI, which is, again, I think, primarily useful as an investor-focused marketing term—and think in fact that such framing has directly help pave the way for the AI firms to concentrate capital and power and to sell their specific vision of automation technology to clients, investors, and the world.

So have many others! It’s worth noting, as has been pointed out by critics and scholars like Emily Bender and Alex Hanna—their new book “The AI Con” is coming out soon, btw—that “AI,” or artificial intelligence, was once deployed as “AGI” is today. AI was a marketing term coined in 1956 by pioneering AI researcher John McCarthy to help get funding for a summer study, and it came to mean a computer system that could, or aspired to, think like a human. To do anything a human could do. AGI, or artificial general intelligence, was coined in the late 90s after the meaning of AI had been diluted, and was more commonly used to describe software programs that could autonomously perform narrow tasks.

Emphasis mine.