With the Arctic warming faster than the global average, researchers at UBC and the University of Edinburgh have made an important discovery about tundra plants and how they are adapting faster than expected to climate change.

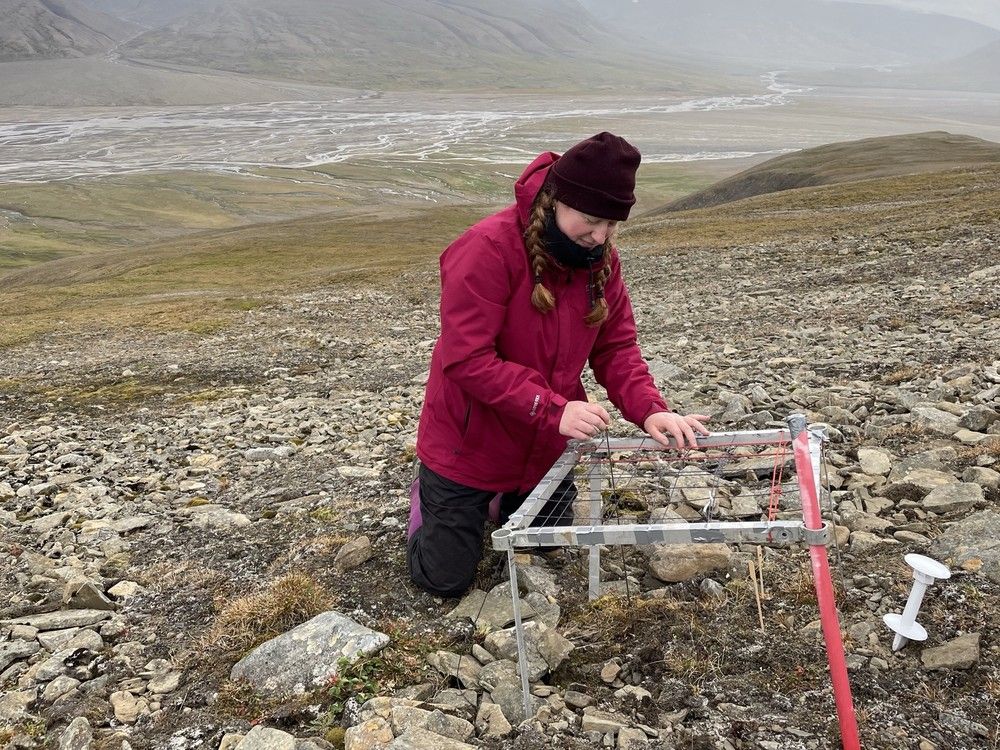

For the joint study, published in the journal Nature , researchers tracked more than 2,000 plant communities over four decades at 45 sites in the Canadian High Arctic, Alaska and Scandinavia, and found that some species thrived while others declined.

They found that some tundra plants like willowy shrubs are able to green up earlier because of longer growing seasons, while other flowering plants are being overshadowed and dying out.

These changes could alter global carbon cycles, according to the long-term monitoring study, which is part of the International Tundra Experiment , a network of researchers examining the impacts of warming on tundra ecosystems.

Scientists say the tundra’s permafrost stores a third of the planet’s carbon. But if the plants on the surface change, that could alter the permafrost, changing how much carbon is being stored.

Isla Myers-Smith, a professor at UBC’s faculty of forestry, led one of the teams at a Yukon Arctic site called Qikiqtaruk, an area that is experiencing dramatic permafrost thaw.

“We’re seeing increases in shrubs, we’re seeing increases in grasses, and we’re seeing a decrease in the bare ground. And all of those vegetation changes together are influencing the habitat for wildlife,” said Myers-Smith.

“What we found was plots where these shrubs over time were becoming quite dominant. We started to see a loss of other species within the plant community, particularly the flowering plants as the shrubs were shading out other species that were growing beneath them.”

While scientists say there is still a lot of work that needs to be done to understand the full implications of the carbon cycle, they know there are affects already happening to the ecosystem.

For example, species of animals like caribou, which is a food source for Indigenous people, rely on lichen in the winter. Myers-Smith said scientists have already documented a decline in lichen as the shrubs increase.

As the habitats become more shrubby, there will also be changes in the bird community from the species that prefer open nesting habitats to ones that prefer the shrubby habitats.

“And then we can think all the way down to insects in the system … like bumblebees which need those flowering plants to get nectar,” she said. “And if you lose the flowering plants from these ecosystems, and particularly the ones that flower at different times across the summer, you can reduce that window when the bumblebees can forage, making life very difficult for an Arctic bumblebee.”

These shifts are reshaping ecosystems in ways scientists don’t yet fully understand, she said, adding that this is why it is vital to track what’s happening so communities can prepare for the consequences. These could include ecosystem collapse, landslides and flooding.

Mariana García Criado, a post-doctoral researcher in tundra biodiversity at the University of Edinburgh, said in a UBC statement that the study sheds light on how climate change is reshaping one of the world’s most fragile ecosystems as it warms at four times the global average.