Indigenous offenders in Prince George are able to avoid criminal charges for minor offences if they’re willing to enter into a new restorative justice program, the first of its kind in Canada, according to the B.C. First Nations Justice Council.

Indigenous people who commit a non-violent crime can, instead of being charged by the RCMP, opt to stay at the Indigenous Diversion Centre for 90 days of treatment, at which point the charges will be dropped, according to council chairperson Kory Wilson.

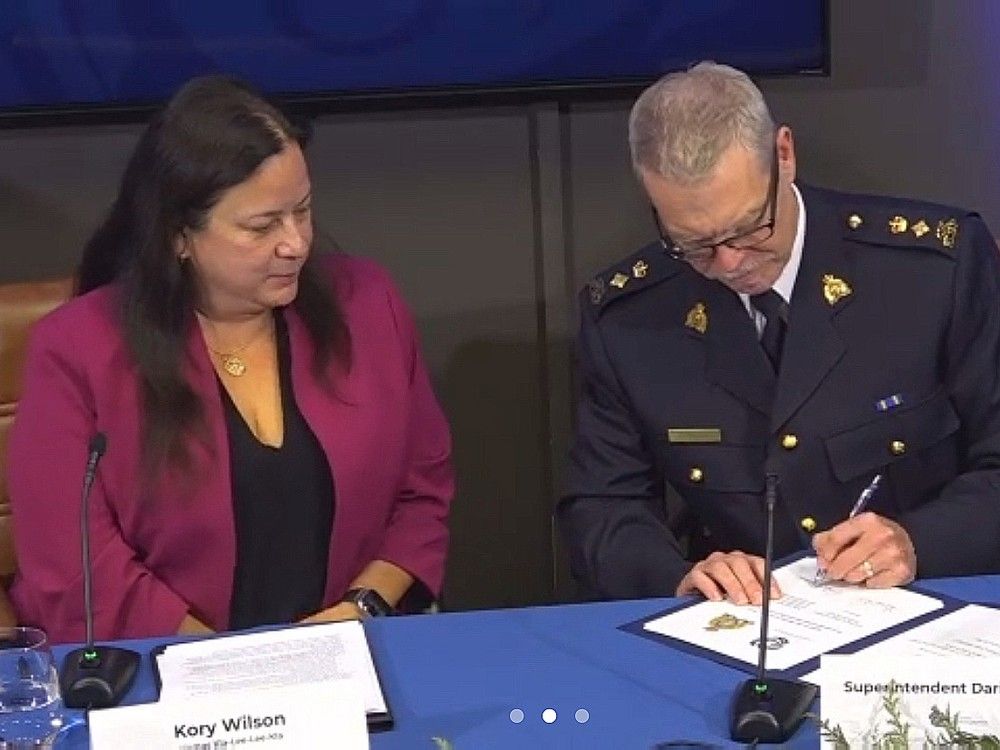

She and Prince George RCMP Supt. Darin Rappel signed a letter of agreement that would allow the diversion of offenders into the centre, where they would complete a program designed to help them address the root cause of their criminal behaviour, such as trauma or addiction, and heal and recover through an Indigenous cultural path that includes spirituality, a news conference was told on Tuesday.

Wilson said the program, which opened in July to offer the same treatment for Indigenous people in the area who finish jail or prison sentences, will now offer “pre-charge” diversion to new offenders.

There are 20 individuals in the post-release program and Wilson said anyone opting to enter either program will be put on a waiting list.

She said the system is designed to address the disproportionate number of Indigenous people who serve sentences for crime and the cost — $282,000 a year — that it takes to keep them incarcerated and “on the negative end of every socio-economic indicator.”

“That’s not acceptable anymore,” she said. “We know that diversion is an option in this country, but it hasn’t been equally applied to Indigenous people.”

Justice Canada released statistics in November 2024 that showed Indigenous people, at just five per cent of the Canadian population, made up 25 per cent of all accused in 2015-16.

And for the decade before that, Indigenous people were 14 per cent more likely to be found guilty than non-Indigenous people, 33 per cent less likely to be acquitted and 55 per cent less likely to have charges withdrawn or dismissed, or to be discharged, it said.

And once convicted, Indigenous people were more likely to receive more serious sentences, such as jail (30 per cent more) or house arrest (11 per cent more), and less likely to receive probation (13 per cent), and to be fined (14 per cent).

She acknowledged that some people call diversion a get-out-of-jail-free card or that it’s easier.

“I don’t know, but anybody who’s grown up with an auntie or a dad like mine, it is not easy if you make a mistake, and our cultures and our systems are about making the person whole,” she said.

“We have to address the fact that in Prince George, only 16 per cent of people are Indigenous and over 60 per cent of the incarcerated people are,” said Terry Yung, minister of state for community safety and a former longtime Vancouver police officer. “Frankly, those numbers are not acceptable.”

Yung said the centre will help reintegrate people who commit crimes back into the community. “We can’t arrest our way out of homelessness” and mental-health issues.

“It might not be the whole solution, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction,” Rappel said.

He said diverting individuals at the point of police contact aims to reduce repeat-offending and improve safety because “enforcement alone does not solve complex social issues.”

The province has for years operated 15 Indigenous Justice Centres that help people once they’re charged to receive the services they need to navigate the justice system, with the same goal of rehabilitation and cultural recovery to reduce recidivism.

But until now, offenders must first plead guilty.

That is the case for the Vancouver drug treatment court in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where offenders must plead guilty before entering into treatment instead of jail.

The province doesn’t keep statistics on those centres.

The diversion centre is funded by the provincial and federal governments.