A man who shot two acquaintances whom he had held resentments against for years was sentenced on Thursday to life in prison for murder without a chance of parole for at least 13 years.

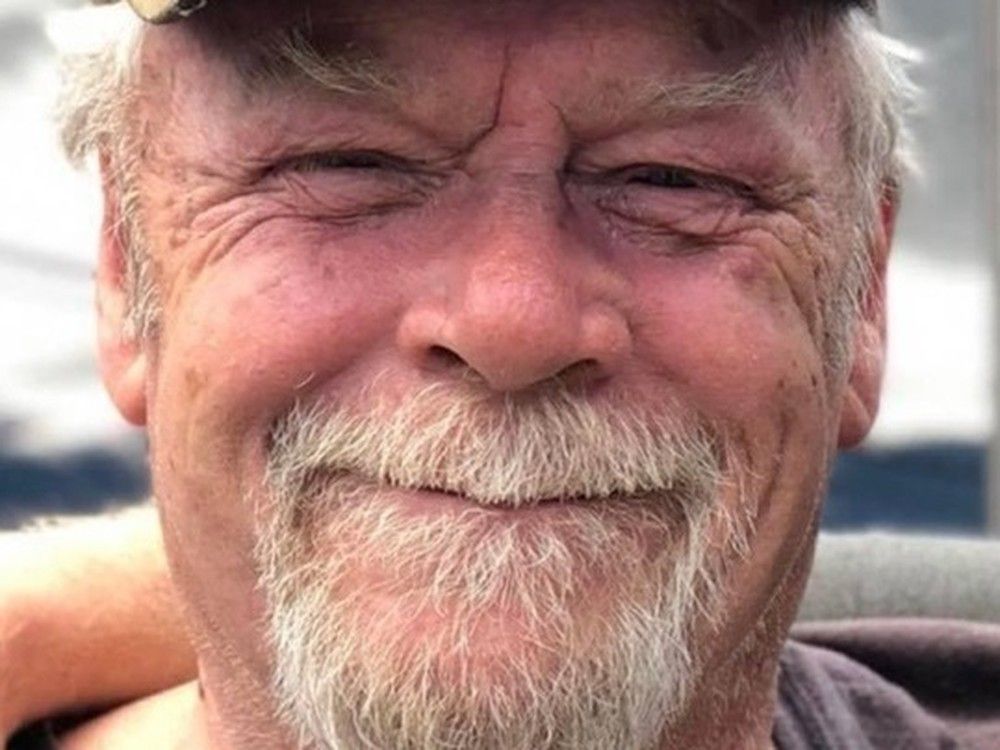

Mitchell McIntyre, who attended the sentencing in a Kamloops courtroom by video, declined to comment when asked if he had anything to say by B.C. Supreme Court Justice Paul Riley.

McIntyre received the life sentence for the second degree murder of his landlord’s partner, Julia Howe, 56, and a grandmother of five, after he pleaded guilty during the trial in November.

He was also sentenced to eight years, to be served concurrently, after pleading guilty to manslaughter using a firearm in the killing of David Creamer, 69, on the same day.

“He killed both of them with the same gun, hours apart,” he said.

The two killings on Feb. 6, 2022, in two different Kootenay towns, Howe in Creston and Creamer in Kimberley, were remarkable because both were ruled accidental by a coroner who said each had died from a fall.

The B.C. Coroner’s Service said this week it was still investigating the deaths and it’s up to the chief coroner to decide if the eventual reports will be released publicly.

Howe’s accidental death became a homicide investigation with the discovery of a bullet in her skull during an autopsy. Creamer’s body by then had been cremated, and without any evidence, McIntyre wasn’t charged with the second killing until after he pleaded guilty to Howe’s murder. He immediately confessed.

Riley had accepted the recommended sentence offered jointly by the prosecutor and McIntyre’s lawyer, which took into a number of aggravating and mitigating factors.

He noted McIntyre, now 66, had no criminal record, had worked his whole life, had suffered physical abuse at home and sexual abuse by a person of authority growing up, suffered from substance abuse disorder, paranoid personality disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, depressive disorder, various medical ailments, including diabetes, and has suffered a heart attack and a stroke.

These factors don’t reduce his moral blameworthiness, said Riley.

“To be clear, Mr. McIntyre certainly knew what he was doing was wrong when he committed the homicides,” but he said he satisfied he acted out in part based on his personality disorders made worse by his substance abuse.

The joint sentencing recommendations take into account McIntyre’s age and poor health, he said.

He also noted McIntyre had a lack of insight into and minimization of his actions and an continuing sense of grievance that could make him a risk to reoffend and he noted his stated intention to not take any of the rehabilitation programming offered in prison.

Howe was shot in the face standing in her bathroom after McIntyre entered her residence to ask about his mail, Riley said.

McIntyre had a long-standing grievance with her about her son’s dog. It was McIntyre’s evidence that she asked him just before he shot her what it was like being a pedophile and he just “f——g lost his mind.”

But Riley noted that insult wasn’t included in his statements at the outset and McIntyre’s lawyer hadn’t explained why his client had gone to visit Howe with a loaded handgun.

McIntyre then drove Kimberley and shot Creamer, whom he owed a longtime unpaid drug debt, in the back of the head without warning.

McIntyre later went to the Creston RCMP detachment and asked to be locked up, but wouldn’t say why, and eventually ended up in hospital. He had made statements to medical staff, some of which were ruled inadmissible, that he had killed a man named David Creamly. He was eventually connected to both deaths.

Riley recounted victim impact statements made by the surviving victims, the family members, to acknowledge the impact the killings continues to have on their lives and on their communities.