B.C. researchers have unlocked the mystery of why billions of sea stars have died over the past decade from B.C. to Alaska and to Mexico.

An international study, published Monday in Nature Ecology and Evolution and led by researchers at the University of B.C., the B.C.-based Hakai Institute and the University of Washington, found that sea star wasting disease is caused by a strain of the bacterium Vibrio pectenicida — one that is related to cholera in humans. Other vibrio species can cause disease in corals and oysters.

Sea star wasting disease is considered one of the largest marine epidemics documented, said Alyssa Gehman, senior author of the study and a marine disease ecologist at the Hakai Institute and UBC.

Gehman said they estimate about six billion sunflower stars have been lost, and that’s just one of 26 species of sea star affected by the disease.

She said the four-year investigation into the cause was challenging because scientists understand very little about sea stars and what types of pathogens they carry.

“The other big challenge is that right after this disease outbreak, it killed many, many sea stars. And to do the type of work that we did, you need to have animals that don’t have the disease, and particularly in sunflower stars, right after the big outbreak there were several years where most had died,” she said.

“We lost 90 per cent of the global population of sunflower stars.”

She said sunflower stars, now considered a critically endangered species, used to be abundant in B.C. and could be found in places like the waters off Stanley Park.

“Now there’s very little chance you will see them.”

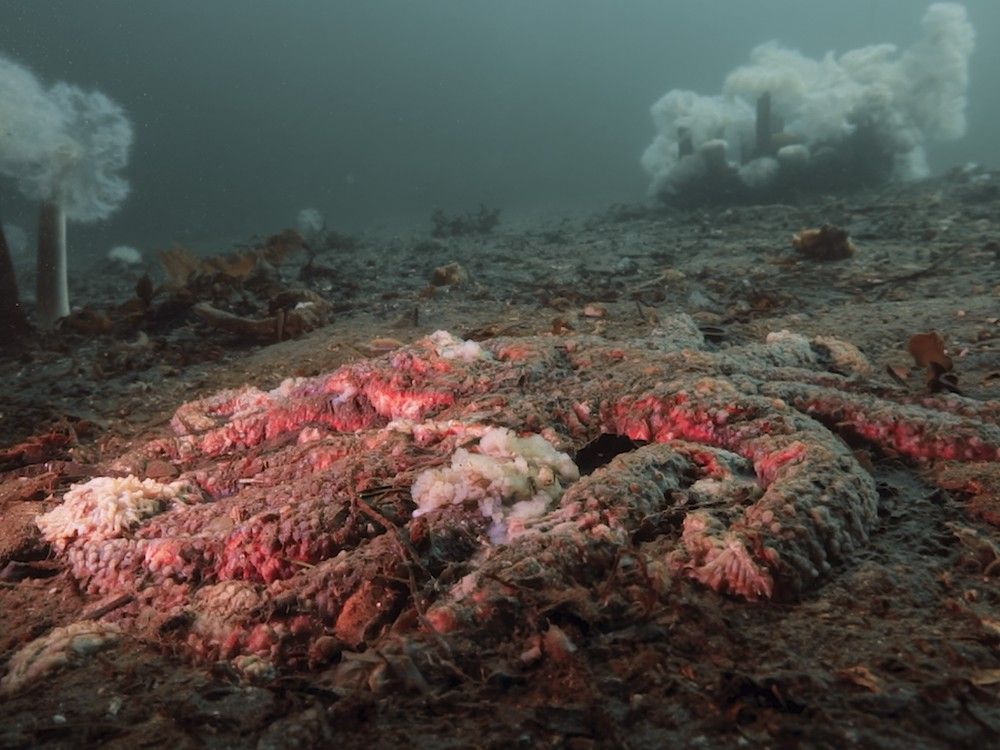

It’s a disease that sounds like something out of a horror film. The sunflower stars start twisting their arms before they deflate, said Gehman.

“They can kind of look like a partially deflated balloon. They’ll have wrinkles in their in their skin, you can sometimes get lesions, or sort of like holes in their dermis, where their organs will fall out … and then the next stage is they’ll lose an arm,” she said.

“The arm will sort of walk away from the body, it’s really horrifying.”

Then, they will lose the rest of their arms and begin to disintegrate.

“They sort of end up just being a goopy pile of former sea star. It’s horrible,” she said.

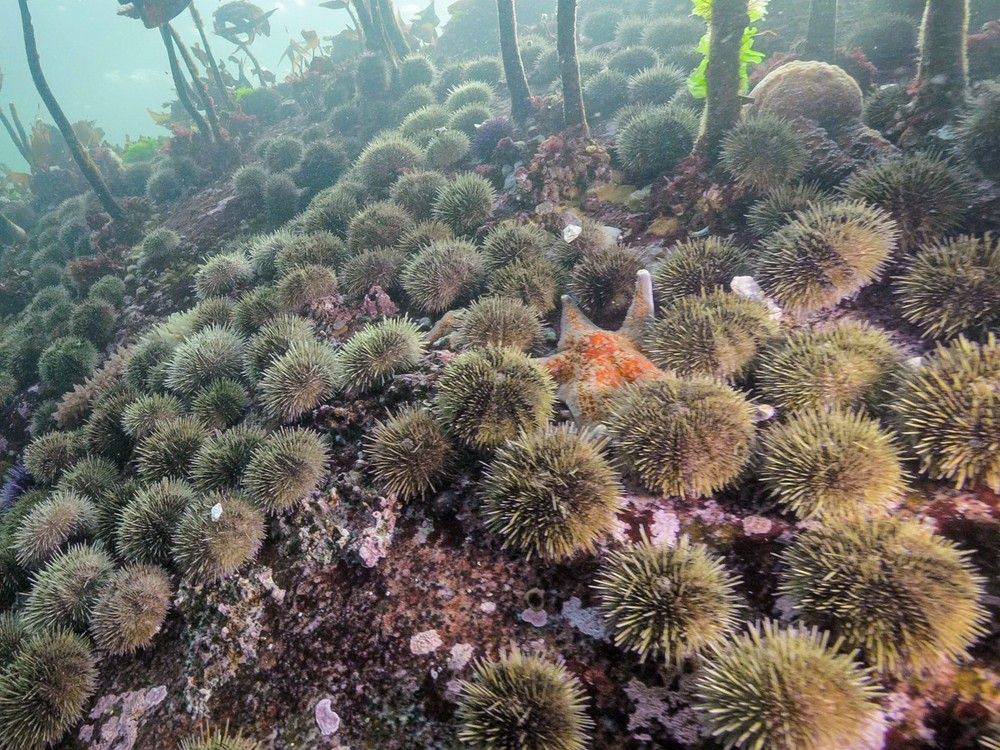

Sea stars are important to the ocean ecosystem because they are what scientists call a keystone species, keeping nature in balance.

With the loss of sea stars, one of their main food sources — urchins — began to thrive and when that happened urchins munched on kelp forests, decimating some of these important carbon sinks.

Kelp forests also provide habitat for an abundance of marine life and protect coastlines from storms.

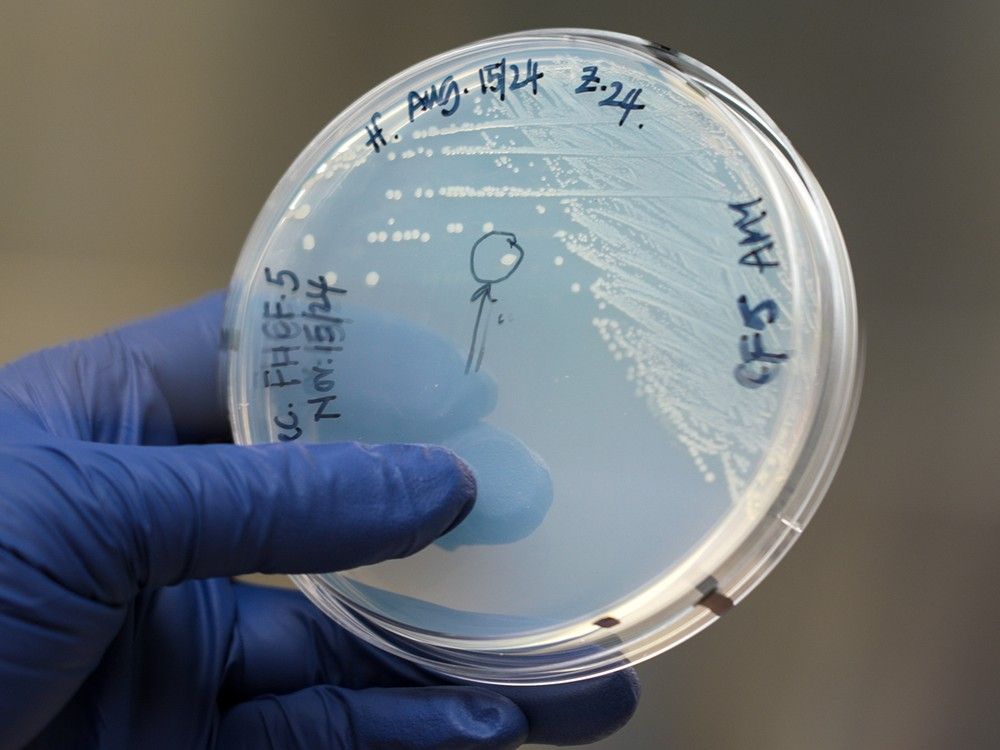

The team of scientists discovered the bacteria was the cause by conducting a series of challenge studies, where they collected healthy sea stars and quarantined them for two weeks to ensure they were disease free. Then they would collect some from the wild showing signs of the start of the disease and conduct experiments on how it was transmitted.

Now that scientists have identified the pathogen that causes the wasting disease, they can start to look into where it came from and what’s causing it.

“It’s exciting that we have the opportunity to actually look into that. And there’s lots of different ways for us to start to piece together what happened, but at this point, we don’t actually know where it came from,” said Gehman.

Gehman said they believe there is a link between rising ocean temperatures and wasting disease because other species of vibrio are known to thrive in warmer water.

Also, she said there have been “refuge areas” where the outbreaks haven’t been as bad and they are in cooler water, such as B.C.’s Central Coast.

“So if the sea stars are in cooler water, it seems like consequences of the disease is lower,” she said, adding more research is needed to understand how temperature plays a role in the wasting disease.

The team can also start to look into a cure. Gehman said there has been success with coral in using probiotics to fight off disease so that might be one avenue for exploration with sea stars.

She said scientists in the U.S. are breeding and raising sunflower stars in the lab in an attempt to try to find stars that are resistant to this pathogen.

“If we find resistant stars, and we’re able to raise them, maybe we can help the populations survive into the future,” she said.

The study was also in collaboration with the Nature Conservancy, the Tula Foundation, the U.S. Geological Survey’s Western Fisheries Research Center, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.