On Aug. 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

An early newspaper account said “the obliterating blast” had “destroyed 60 per cent of the Japanese city.”

“Practically all living things — human and animal — were ‘literally seared to death’ by the new weapon loosed against the industrial and military city,” said another story in the Aug. 8 Vancouver Daily Province.

But the Japanese failed to surrender immediately. And the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki Aug. 9.

Many people were “vaporized” in the atomic blasts, so a death count was difficult. But a 2020 article in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists online magazine said the “most credible estimates” were that 70,000 to 140,000 people were killed in Hiroshima, and 40,000 to 70,000 were killed in Nagasaki — a combined death count between 110,000 and 210,000.

Details of the devastation on the ground were not immediately available. So the initial newspaper stories Aug. 6 focused on the bomb, which an Associated Press story contained more power than 20,000 tons of TNT.

“The bomb produces more than 2,000 times the blast of the largest bomb ever used,” said the AP story.

Both the Vancouver Sun and the Province said the power of the atomic bomb was comparable to seven of the blasts that devastated Halifax after a munitions ship blew up there on Dec. 6, 1917, killing 1,500, injuring 4,000 and leaving 20,000 people homeless.

American president Harry Truman said his country had spent $2 billion on the atomic bomb project.

“It is the harnessing of the basic power of the universe,” Truman stated on Aug. 6. “The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East.”

The London Daily Mail reported Aug. 7 that the Japanese would receive a 48-hour ultimatum “threatening to atom-bomb her into oblivion unless she surrendered unconditionally.”

But it didn’t, so a different type of atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Vancouver newspapers were openly racist during the Second World War, routinely referring to the Japanese as “Japs.” But local coverage of the atomic bomb was more restrained than in American papers.

“Truman Tells Japs: ‘GIVE UP OR WIPED OUT BY ATOMIC BOMB’,” screamed the front-page headline in the “War Extra” of the Aug. 7 Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

As jingoistic as some stories were, reports of the devastation and potential problems of radioactivity soon began to crop up.

A William Tyree story in the Aug. 8 Sun reported on a Radio Tokyo broadcast that said: “Inhabitants were killed by blast, fire and crumbling buildings. Most bodies were so badly battered that it was impossible to distinguish between the men and the women.

“Radio Tokyo said both the dead and wounded had been burned beyond recognition.”

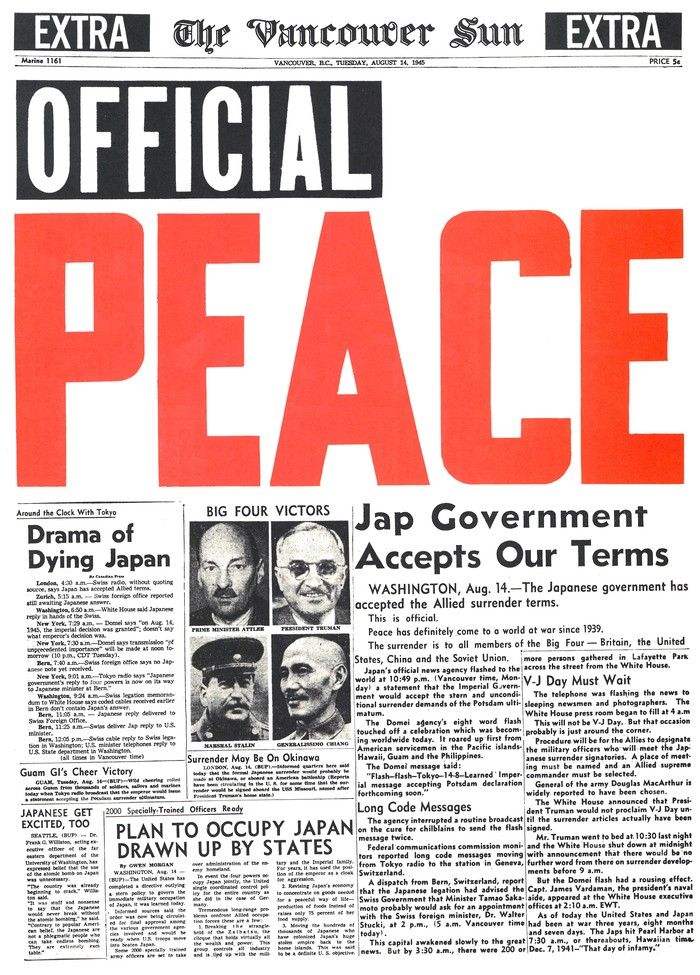

The Japanese finally surrendered Aug. 15. B.C. is 16 hours behind Tokyo, so the news reached Vancouver on the afternoon of Aug. 14.

The Vancouver Sun printed an Extra edition within minutes of the Japanese surrender. It had a simple headline: “OFFICIAL” in white letters against a black background, and “PEACE” in giant red letters.

There were no photos released of the atomic blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the time. The Chicago Tribune printed photos of atomic blasts in New Mexico on Aug. 18, but not of the bombs dropped on Japan.

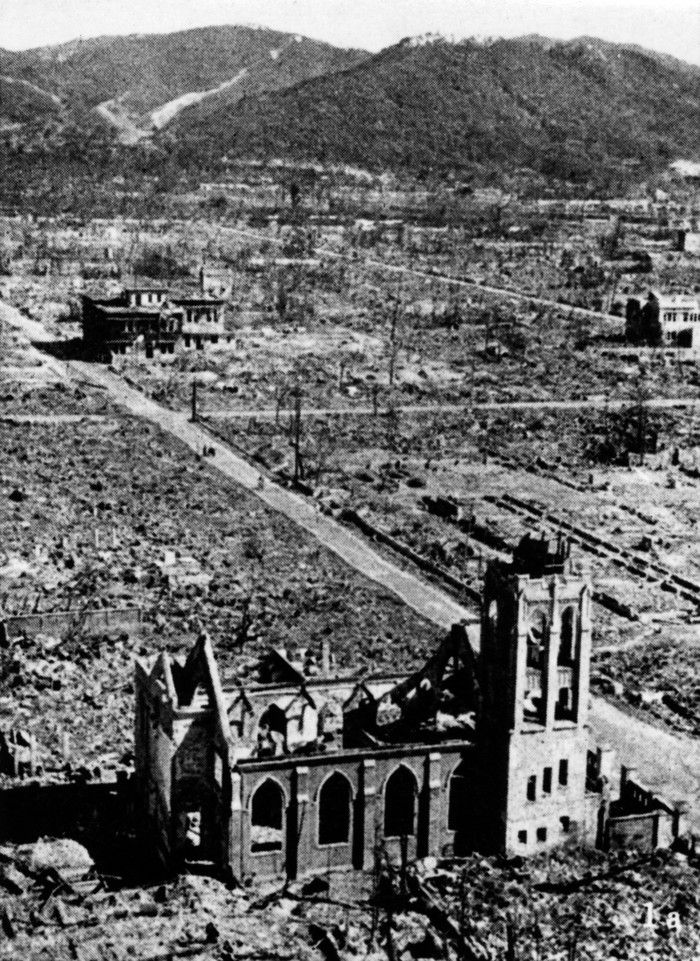

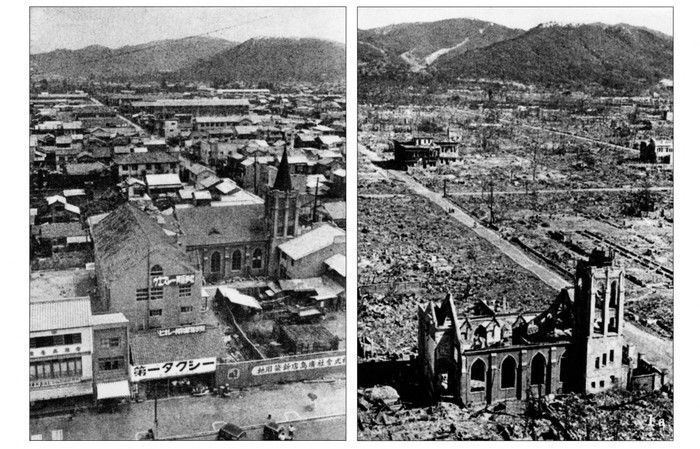

Photos taken by Japanese photographers of the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were first printed in the Province on Sept. 4, alongside a report by Vern Haugland of the Associated Press. It was headlined Hiroshoma Atomic City of the Dead.

But the photos didn’t show the devastation on people, probably because the U.S. occupation forces didn’t want them to be shown. The current edition of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has a story on Japanese photojournalist Yoshito Matsushige , who was in Hiroshima when the bomb was dropped.

Matsushige took five chilling photographs Aug. 6, the only known photos taken in Hiroshima that day. Two show a group of junior high school students with “shredded clothing, severe burns and peeling skin.”

“I clearly remember how the viewfinder was clouded over with my tears,” Matsushige later said.

Matsushige’s photos weren’t widely shown until the U.S. occupation ended in 1952.