5 min read

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)

The review takes a close look the final flight of the agency’s Ingenuity Mars Helicopter, which was the first aircraft to fly on another world.

Engineers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and AeroVironment are completing a detailed assessment of the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter’s final flight on Jan. 18, 2024, which will be published in the next few weeks as a NASA technical report. Designed as a technology demonstration to perform up to five experimental test flights over 30 days, Ingenuity was the first aircraft on another world. It operated for almost three years, performed 72 flights, and flew more than 30 times farther than planned while accumulating over two hours of flight time.

The investigation concludes that the inability of Ingenuity’s navigation system to provide accurate data during the flight likely caused a chain of events that ended the mission. The report’s findings are expected to benefit future Mars helicopters, as well as other aircraft destined to operate on other worlds.

Final Ascent

Flight 72 was planned as a brief vertical hop to assess Ingenuity’s flight systems and photograph the area. Data from the flight shows Ingenuity climbing to 40 feet (12 meters), hovering, and capturing images. It initiated its descent at 19 seconds, and by 32 seconds the helicopter was back on the surface and had halted communications. The following day, the mission reestablished communications, and images that came down six days after the flight revealed Ingenuity had sustained severe damage to its rotor blades.

What Happened

“When running an accident investigation from 100 million miles away, you don’t have any black boxes or eyewitnesses,” said Ingenuity’s first pilot, Håvard Grip of JPL. “While multiple scenarios are viable with the available data, we have one we believe is most likely: Lack of surface texture gave the navigation system too little information to work with.”

The helicopter’s vision navigation system was designed to track visual features on the surface using a downward-looking camera over well-textured (pebbly) but flat terrain. This limited tracking capability was more than sufficient for carrying out Ingenuity’s first five flights, but by Flight 72 the helicopter was in a region of Jezero Crater filled with steep, relatively featureless sand ripples.

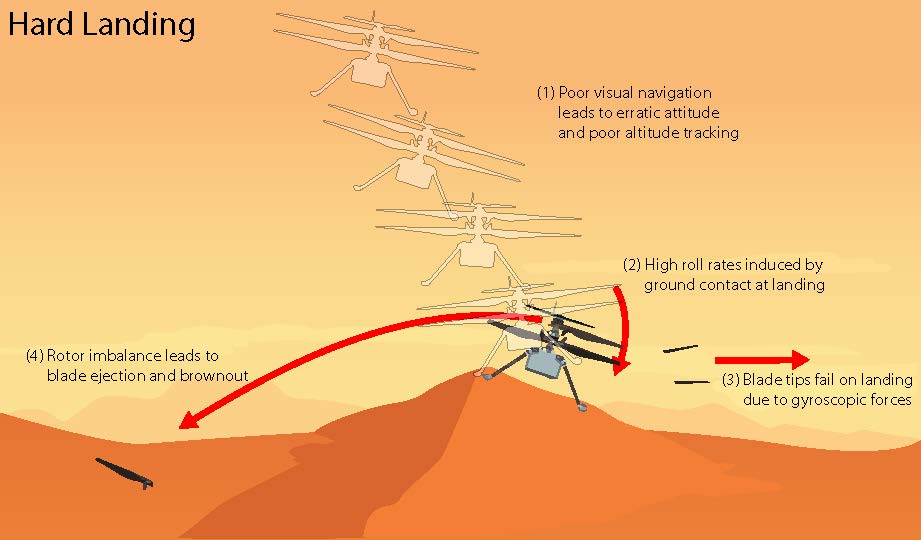

One of the navigation system’s main requirements was to provide velocity estimates that would enable the helicopter to land within a small envelope of vertical and horizontal velocities. Data sent down during Flight 72 shows that, around 20 seconds after takeoff, the navigation system couldn’t find enough surface features to track.

Photographs taken after the flight indicate the navigation errors created high horizontal velocities at touchdown. In the most likely scenario, the hard impact on the sand ripple’s slope caused Ingenuity to pitch and roll. The rapid attitude change resulted in loads on the fast-rotating rotor blades beyond their design limits, snapping all four of them off at their weakest point — about a third of the way from the tip. The damaged blades caused excessive vibration in the rotor system, ripping the remainder of one blade from its root and generating an excessive power demand that resulted in loss of communications.

Down but Not Out

Although Flight 72 permanently grounded Ingenuity, the helicopter still beams weather and avionics test data to the Perseverance rover about once a week. The weather information could benefit future explorers of the Red Planet. The avionics data is already proving useful to engineers working on future designs of aircraft and other vehicles for the Red Planet.

“Because Ingenuity was designed to be affordable while demanding huge amounts of computer power, we became the first mission to fly commercial off-the-shelf cellphone processors in deep space,” said Teddy Tzanetos, Ingenuity’s project manager. “We’re now approaching four years of continuous operations, suggesting that not everything needs to be bigger, heavier, and radiation-hardened to work in the harsh Martian environment.”

Inspired by Ingenuity’s longevity, NASA engineers have been testing smaller, lighter avionics that could be used in vehicle designs for the Mars Sample Return campaign. The data is also helping engineers as they research what a future Mars helicopter could look like — and do.

During a Wednesday, Dec. 11, briefing at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting in Washington, Tzanetos shared details on the Mars Chopper rotorcraft, a concept that he and other Ingenuity alumni are researching. As designed, Chopper is approximately 20 times heavier than Ingenuity, could fly several pounds of science equipment, and autonomously explore remote Martian locations while traveling up to 2 miles (3 kilometers) in a day. (Ingenuity’s longest flight was 2,310 feet, or 704 meters.)

“Ingenuity has given us the confidence and data to envision the future of flight at Mars,” said Tzanetos.

More About Ingenuity

The Ingenuity Mars Helicopter was built by JPL, which also manages the project for NASA Headquarters. It is supported by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley and NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, provided significant flight performance analysis and technical assistance during Ingenuity’s development. AeroVironment, Qualcomm, and SolAero also provided design assistance and major vehicle components. Lockheed Space designed and manufactured the Mars Helicopter Delivery System. At NASA Headquarters, Dave Lavery is the program executive for the Ingenuity Mars helicopter.

For more information about Ingenuity:

https://mars.nasa.gov/technology/helicopter

News Media Contacts

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Karen Fox / Molly Wasser

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1600

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / molly.l.wasser@nasa.gov

2024-171